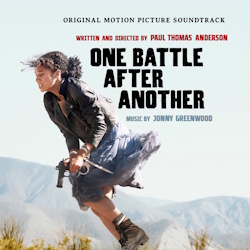

ONE BATTLE AFTER ANOTHER – Jonny Greenwood

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

One of the most popular and critically acclaimed movies of 2025, One Battle After Another is a black comedy action-thriller written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, loosely inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland. The film stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Bob Ferguson, a former left-wing political revolutionary from an underground militant group called the French 75. Early in the film, the French 75 carry out a bold operation at the Mexico–US border, freeing apprehended immigrants and sparking conflict with ruthless military officer Steven Lockjaw (Sean Penn), who has a bizarre sexual obsession with Bob’s partner Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor). After Perfidia is arrested for murder, Lockjaw arranges for her to avoid prison in exchange for ratting out her comrades, forcing Bob to flee. Sixteen years later, Bob is living off-grid, paranoid, and raising his teenage daughter Willa (Chase Infiniti) far from the revolution. Things change for Bob when a still-obsessed Lockjaw discovers his location, and he and Willa are separated. Desperately trying to rescue his daughter, Bob is forced to get back in touch with his old French 75 compatriots – including Sergio St. Carlos (Benicio del Toro), a martial arts instructor who also runs underground support networks – before Lockjaw finds her.

The film is a sharp social satire that pokes at several incredibly prescient topics in American political culture, and critiques extremism and ideological rigidity on all sides of the political spectrum. It looks at the prevalence of white supremacy in American politics, the military, and law enforcement; how absurd political obsession can become; how revolutionaries are never purely heroic, and can often undermine their own goals with their actions; and comments on the dangers of state power unchecked by accountability. It does all this with a vein of absurdly dark humor that laughs at the fact that the main character is an old, out-of-shape stoner in a bathrobe who just wants to be left alone, a modern version of The Dude from The Big Lebowski.

The score for One Battle After Another is by British composer Jonny Greenwood. This is his sixth collaboration with director Anderson, after There Will Be Blood in 2007, The Master in 2012, Inherent Vice in 2014, Phantom Thread in 2017, and Licorice Pizza in 2021, almost all of which also received significant critical acclaim and some kind of awards love. Greenwood is a fascinating composer; of course, his background is in the experimental art rock and electronica of his band Radiohead, but since he began working in film in the early 2000s he has developed into a darling of the ‘Indiewire set,’ writing a series of scores which combine contemporary orchestral elements with minimalist emotional content, but also a harshly aggressive modernist attitude that sometimes drives his work into the realms of the atonal. I really like some of his scores – especially Phantom Thread – but I find others very difficult to grasp, mostly because his musical aesthetic and his approach to what film music actually is and what it is supposed to achieve is often quite different to mine.

One Battle After Another is very much an example of what I’m talking about. Greenwood was involved with the film from the earliest stages of production, and wrote quite a lot of his music based solely on the script, which was then played to the cast on-set during production so that they could get an understanding of the tone of the film. The music he ultimately wrote is a wildly eclectic collision of styles, influences, and approaches, some of which work, and some of which absolutely do not, resulting in a score which is deeply divisive depending on your point of view.

One Battle After Another is very much an example of what I’m talking about. Greenwood was involved with the film from the earliest stages of production, and wrote quite a lot of his music based solely on the script, which was then played to the cast on-set during production so that they could get an understanding of the tone of the film. The music he ultimately wrote is a wildly eclectic collision of styles, influences, and approaches, some of which work, and some of which absolutely do not, resulting in a score which is deeply divisive depending on your point of view.

Many critics liked it a lot in film context, variously describing it as “jolting, jangling, nerve-shredding,” “truly bonkers,” “marvelously uneasy,” “a metronome of suspense,” and “veering between manic percolation and grandly operatic surges of synth”. All these descriptions were intended by their writers to be positive. My reaction to the music in context was markedly different, and was mostly influenced by a 25-minute sequence in the middle of the film, where Bob and Sergio are frantically fleeing through a city, across rooftops and through tunnels, trying to evade Lockjaw’s military team. Greenwood scored this scene with an extended, incessant, piano motif that, for long stretches, is literally nothing more than a single piano key being struck, over and over and over. Conceptually, I understand what the aim was: Greenwood was trying to create a sense of tension, unease, and increasing panic, and on some level he actually succeeds with this, but in the moment I hated it.

Only once prior to this film have I ever wanted to leave a movie theater because I felt the music was ruining the movie, and that was because of Daniel Lopatin’s score for Good Time in 2017. This was the second time. The music in that 25-minute sequence was just so relentlessly aggressive, shrill and discordant, and was so distracting, that I felt myself being pulled out of the film because I was hyper-aware of how much I disliked it, to the extent that I never got back into it. The whole thing clouded the entire movie-going experience for me, including all the other music in the entire rest of the film, none of which I could recall afterwards.

This also throws into sharp relief the difference between the in-context effectiveness of the score, and the subsequent album listening experience, because the two are poles apart. As I said, the in-context experience of the music was entirely undermined for me by the 25-minute piano chase sequence cue, but this cue is not on the accompanying soundtrack album, and I found that when I listened to the music that is on the album, I had absolutely zero memory of hearing it in the film. This is something that virtually never happens to me, but underlines just how negatively that one sequence affected me.

It’s also interesting that I found the soundtrack album listening experience to be much more positive. It’s actually one of Greenwood’s more approachable scores; it’s still full of those avant-garde classical sounds that he loves so much, but there’s also a great deal of variety too, both in the instrumental palette Greenwood uses, and in some of the thematic ideas. Stylistically there is a lot of influence from the 1970s, especially the iconic crime thriller scores written by composers like David Shire, Jerry Fielding, Lalo Schifrin, and others, which blended aggressive orchestral sounds with influences from jazz.

The ensemble here is led by the low-key symphonic sound of the London Contemporary Orchestra, which is then bolstered by prominent solos featuring violin, cello, a prepared piano, a variety of percussion items, and an ondes martenot, the latter of which Greenwood plays himself. Emotionally the music is agitated and jittery, often blending off-kilter, discordant sounds – staccato pianos, col legno strings – with smoother, warmer tones that sometimes feel faintly romantic. The jittery sounds are generally associated with DiCaprio’s character Bob, who is often strung out and paranoid, while the softer sounds tend to be associated with Bob’s daughter Willa. Their relationship, and Bob’s love for her, is a key driver of the entire plot.

Cues like the title track “One Battle After Another,” and subsequent tracks like “The French 75,” “I Need the Greeting Code,” “Ocean Waves,” and “Like Tom Fkn Cruise” are prominent examples of the staccato piano and plucked strings material for Bob, and are the closest, tonally, to the 25-minute piano chase sequence. The moodily romantic string writing that offsets against the piano during “One Battle After Another” is unexpectedly emotional. The insistent, oddly metered piano writing in “The French 75” is actually quite fascinating, as is the way it combines with a set of eerie extended string harmonics and urgent cello pulses in “I Need the Greeting Code”. “Ocean Waves” blends the chaotic piano with dissonant percussion, shrill woodwind trills, and surges of sickly-sounding brass, in a way that sometimes feels a little Stravinsky-esque. Later, florid violin textures and hectic pizzicato strings combine with frenzied piano chords in “Like Tom Fkn Cruise,” giving the cue a mounting sense of chaos and panic.

Cues like “Baby Charlene” and “Guitar for Willa” focus on the music for Bob and Perfidia’s daughter and are much more traditionally melodic; Charlene/Willa grew up after the ‘revolution,’ and never knew her mother, so the sense of urgent chaos that dominates the music of her parents is mostly absent from hers – at least until her peace is shattered by Lockjaw’s arrival. In “Baby Charlene” her theme has a funky, offbeat, slightly tropical sound, and has a main melodic line that moves between an ondes martenot and a lush bank of layered strings. In “Guitar for Willa” her theme is carried by a set of gently romantic Spanish guitar flourishes that are actually quite lovely.

“Baktan Cross” contains the most prominent statement of the menacing, animalistic drone that represents Sean Penn’s brutal, amoral, but ultimately wretched antagonist character Lockjaw. Other moments worth noting include the ominous pianos and dark string writing for the unapologetically antagonistic revolutionary “Perfidia Beverly Hills,” the off kilter, warped twangy guitar textures of “Mean Alley” (which was co-written by Greenwood with his Radiohead bandmate Thom Yorke), and the mellifluous classical strings of “Battle After Battle”.

“Sisters of the Brave Beaver” is a tense, tightly-wound exercise in sharp percussion writing offset by stark, complicated piano rhythms, representing the fictional convent of nuns who take in Willa and help shield her from Lockjaw and his goons. The subsequent “Operation Boot Heel” cleverly combines three distinct ideas – drunken, slurred pianos for the Sisters, tropical percussion for Willa, low-key drones for Lockjaw – for the scene where the Sisters of the Brave Beaver’s compound is stormed by the military.

“Avanti Q” is associated with the bounty hunter character played by Eric Schweig, who is charged with capturing Willa, and is another festival of fluttering classical guitars. “River of Hills” – which underscores the conclusive car chase through the desert where John Hoogenakker’s relentless assassin Tim Smith stalks Willa like a shark homing in on its prey – is full of driving snare drums and intense, brutal, throbbing percussive strings, and is a gripping exercise in Herrmann-esque suspense and relentless inevitability. “Trust Device” is sort of a bonus source music track, as it is an extended version of the unnerving, glassy, synthy, dance-like music that plays when Willa is using her ‘trust device’– a secure communication scanner used to verify identities. The final cue, “Trio for Willa,” returns to the theme for that character and is a soft, elegant, but slightly mournful arrangement for a string trio, one violin, one viola, and one cello .

The film also features two laid-back instrumental cues written by composer Jon Brion, who previously scored several of Anderson’s earlier films, including Magnolia in 1999 and Punch-Drunk Love in 2002. The two cues, “Bunker Bumper” and “Global Bully,” actually come from an archive of unused music that Brion had written for Anderson several years previously, for no particular project, and which Anderson uses periodically to plug musical gaps in his films. “Global Bully” actually underscores the emotional finale of the film when Willa reads a letter from Perfidia, in which she apologizes for her actions and promises to someday reunite with her family. Neither cue is included on the film’s soundtrack album.

So; look. One Battle After Another is a perfect example of the dichotomy that can sometimes exist in film music where the in-context movie experience of a score is vastly different from the album listening experience. In the wake of the 25-minute piano chase sequence, as I was finally leaving the theater, I had convinced myself that I hated this score. I had genuinely wanted to get up and leave during it, and my viscerally negative reaction to the music in that moment clearly soured my memory of the whole thing. I remembered nothing else about any of the other music in context – just my discomfort and extreme annoyance during that one, endless, interminable scene.

But then, hearing the album in isolation, the other things that Greenwood was doing for the film become clearer, and as a piece of recorded music, there is a lot to like. Greenwood’s contemporary avant-garde orchestral writing, with its emphasis on tortured strings, combines well with the dissonant and insistent piano motifs for Bob, the warmer classical guitar sounds for Willa, and one or two impressively brutal action sequences, especially the rampaging cue for the final car chase. As I mentioned before, a lot of this music is actually much more accessible and tonal than many of his other previous works – certainly more so than There Will Be Blood or The Master, for example – and so for Greenwood newcomers who might be a bit daunted by him, or apprehensive of what he’s all about, One Battle After Another is actually a good way to get in touch with his music.

I still don’t think this score worthy of all the acclaim it is receiving from awards bodies – as is usually the case these days, it appears to be being swept along for the ride on the rollercoaster of critical love for the film itself. Frankly, I don’t really feel that the film is as groundbreaking or important as people are making it out to be, either, but I’m not going to go into all that now. However, I will concede that there is quite a lot of good, interesting music to be discovered here, and had it not been for that frickin’ piano, I might have been inclined to realize this sooner.

Buy the One Battle After Another soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- One Battle After Another (3:09)

- The French 75 (1:30)

- Baktan Cross (2:59)

- Baby Charlene (3:16)

- Perfidia Beverly Hills (2:37)

- Mean Alley (2:46)

- I Need the Greeting Code (4:19)

- Ocean Waves (2:34)

- Guitar for Willa (3:35)

- Battle After Battle (2:36)

- Sisters of the Brave Beaver (3:01)

- Like Tom Fkn Cruise (3:25)

- Operation Boot Heel (2:12)

- Avanti Q (1:07)

- River of Hills (2:07)

- Greeting Code Reprise (0:53)

- Trust Device (3:51)

- Trio for Willa (3:04)

Nonesuch Records (2025)

Running Time: 48 minutes 53 seconds

Music composed by Jonny Greenwood. Conducted by Hugh Brunt. Performed by the London Contemporary Orchestra. Orchestrations by Jonny Greenwood. Recorded and mixed by Graeme Stewart, John Barrett and Lewis Jones. Edited by Graeme Stewart. Album produced by Jonny Greenwood and Graeme Stewart.

-

February 24, 2026 at 11:55 amOscar 2026. Análisis de Categorías: Mejor Música/ Score – Oscar Times