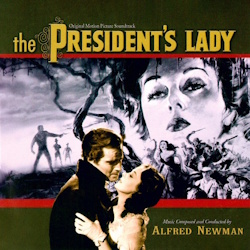

THE PRESIDENT’S LADY – Alfred Newman

GREATEST SCORES OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

GREATEST SCORES OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Original Review by Craig Lysy

The 1951 novel The President’s Lady by Irving Stone caught the attention of 20th Century Fox management as it offered a tale of one of America’s most dynamic and controversial presidents, Andrew Jackson, including his romance with Rachel Donelson. Playwright John Patrick was hired to adapt the novel and write a screenplay. Management was satisfied, and the project was given the green light to move into production. Sol. C. Siegel was placed in charge of production with a $1.475 million budget, and Henry Levin was tasked with directing. A stellar cast was hired, including Charlton Heston as Jackson, Susan Hayworth as Rachel Donelson, John McIntire as John Overton, and Fay Bainter as Mrs. Donelson.

The story begins in 1789 with a chance meeting of Mrs. Rachel Robards and the young Tennessee Attorney General Andrew Jackson. Rachel is estranged from her husband and Jackson finds himself falling in love. Complications arise with the return of her wayward husband, who demands she return home with him. She does so reluctantly only to find he has been having an affair with their slave girl. After much conflict and intrigue, Rachel secures a divorce and she and Andrew marry. Jackson’s political fortunes rise as he as he serves in congress as a Senator and becomes a national hero when he wins the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812. He continues his political ascent and eventually gains the presidency in 1828. Despite his heroism and service, the stain of adultery plagues Rachel, who loses her health and dies on the eve of Jackson’s inauguration. The film lost $125,000, and critical reception was tepid. The film received two Academy Award Nominations for Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design.

Alfred Newman, Director of Music at 20th Century Fox took on the assignment. I believe that upon viewing the film that Newman understood that he had a broad canvass on which to compose. The film’s narrative offered a classic tale of a man’s rise to power, one with many challenges, which through sheer force of will, he overcame. He rose from humble beginnings to become Attorney General of Tennessee, Congressman, Senator, War Hero, Military Governor of Florida, finally achieving the pinnacle of power, President of the United States. Throughout it all, and always at his side was the love of his life, Rachel. Yet she, as a divorcee, and he by association were constantly beset by the scandal of adultery. In the end, Rachel’s health failed from years of onslaught. For Newman, this rise to power, and tragic romance, demanded musical storytelling.

For his soundscape, Newman composed five themes, and a number of motifs. Andrew’s Theme supports our hero and protagonist Andrew Jackson, and when in battle, the troops under his command. Expressed in ABA form, the A Phrase offers a stately drum empowered marcia nobile, which speaks to the dignity of the office of president. The B Phrase is much more expressive, espousing pride and Andrew’s indomitable spirit. Rachel’s Theme offers graceful elegance, and is expressed with two repeating four-note phrases, with a concluding six-note phrase. Expressed by woodwinds tenero, it emotes with a soft strolling sensibility. Within the notes, I discern an undercurrent of sadness, a long-suffering romanticism as her life is difficult and frequently beset by malevolent people and events beyond her control. Over time, her theme evolves into a Love Theme for her and Andrew, expressed as a beautiful romanza. For our villain, Lewis’ Theme supports his identity as her jealous, possessive and adulterous husband. Newman provides a dark, menacing and oppressive construct with two seven-note phrases, which appear to be mirror images.

For his soundscape, Newman composed five themes, and a number of motifs. Andrew’s Theme supports our hero and protagonist Andrew Jackson, and when in battle, the troops under his command. Expressed in ABA form, the A Phrase offers a stately drum empowered marcia nobile, which speaks to the dignity of the office of president. The B Phrase is much more expressive, espousing pride and Andrew’s indomitable spirit. Rachel’s Theme offers graceful elegance, and is expressed with two repeating four-note phrases, with a concluding six-note phrase. Expressed by woodwinds tenero, it emotes with a soft strolling sensibility. Within the notes, I discern an undercurrent of sadness, a long-suffering romanticism as her life is difficult and frequently beset by malevolent people and events beyond her control. Over time, her theme evolves into a Love Theme for her and Andrew, expressed as a beautiful romanza. For our villain, Lewis’ Theme supports his identity as her jealous, possessive and adulterous husband. Newman provides a dark, menacing and oppressive construct with two seven-note phrases, which appear to be mirror images.

There are two Indian identities; one for the Creek warriors and one for Andrew and Rachel’s adopted Creek son, Lincoya. The Creek, as Indians, are cast as the villains, and Newman supports with a primary woodwind line buttressed by muted horns, menacing drums, joined by a contrapuntal three-note motif. In battle their theme becomes an anthem of war. Lincoya’s Theme evokes child-like innocence, which is strongly draped with indigenous Indian auras and cultural sensibilities. His theme is carried by flute delicato, soft drum tones, and strummed harp. Lastly, a number of traditional, folk and classical pieces were infused into his soundscape to provide the requisite cultural sensibilities, many of which were composed and/or arranged by Urban Thielmann.

Cues coded (*) contain music not found on the album. (*) “Logo” opens the film with Newman’s iconic 20th Century Fox fanfare. “Main Title” offers a score highlight where Newman introduces his two primary theme and sets the tone of the film. It commences with the flow of the opening credits against a woven background displaying the Presidential Eagle emblem. Newman introduces Andrew’s Theme, a stately drum empowered marcia nobile. At 0:55 we flow into the film proper as we see Andrew riding into a village supported by narration by Hayward: “The year was 1789. The day was like any other day. The man like any other man. Time alone was to prove the difference. The morning this man appeared at the top of the hill and rode into our valley marked the beginning. And in the end, I was to realize that nothing really important had ever happened to me before this day. I was to know this stranger as no one else was to know him. It’s been said that every man has two sides… The side he shows to the world, and the side he shows to the woman he loves. This was the side I was destined to see, and this was the day of the beginning”.

Newman introduces Rachel’s Theme, which offers graceful elegance, and is expressed by woodwinds tenero with a strolling sensibility. At 1:33, a bridge of harp glissandi usher in a gentile reprise of Andrew’s Theme as he ties up his horse and walks to the inn door and knocks. “Rachel” offers a score highlight with pleasant interplay of Rachel and Andrew’s Theme. Andrew’s knocks are answered by other knocks. He is perplexed and looks through the window to see a beautiful woman hammering pictures on a wall. She turns, sees him, and as he turns aways, a spirited rendering of her theme propels her off a stool. At 0:16 an interlude of no music begins as she greets him. His apology disarms her, and he explains he is the new lawyer that will be joining John Overton’s practice. He asks to rent a room, but she says only her mother may rent rooms. She suggests that he stay at John’s cabin until her mother returns. Music rejoins at 0:17 with the gentile, variation of her theme as she extends an invitation to supper. As they stroll to John’s cabin, a pleasant and gentile strolling ABA rendering of Andrew’s Theme supports.

(*) “Possum Up a Gum Stump” reveals a caller playing a fiddle as the villager dance with merriment at a social. Andrew and Rachel are enjoying the dance when a tall dark-haired man arrives, causing several people to raise their eyebrows. He walks over, takes Rachel by her arm, and says he to Andrew that he would like to speak to his wife. Rachel introduces a surprised Andrew to Lewis Robards, her husband, and they depart to a corner of the room. The dance music continues to play in the background under their dialogue. We find that they are estranged, that he sent her back to her family out of jealousy, and that he is here to make amends. He hugs here, and says he wants her back again, but she does not reciprocate his hug. The next day at breakfast Andrew and John find out that Rachel had returned to Harrisburg, with Mrs. Donelson adding that a wife’s place is with her husband. “The Robards” reveals Lewis and Rachel arriving home in a rainstorm, with Newman introducing an ominous Lewis’ Theme infused with the turbulence of the storm. At 0:25 a distressed Rachel’s Theme carries her upstairs to Lewis’ mother, whom they have been told is ailing. They reacquaint and we bear witness to genuine affection between the two. At 1:09 Rachel’s Theme shifts to a solo oboe triste as she relates, she did not leave, but was sent away. Mother encourages her to be strong, and bear a son as soon as possible. At 1:51 Rachel’s Theme becomes foreboding as says she has to change out of her wet clothes, and Mother frets as to why Lewis has not come to see her. Rachel walks out on to the landing at the top of the stairs and her theme at 2:16 becomes aggrieved when she hears the slave maid fret to Sam; “What if she finds out?” from the landing she overhears Lewis ‘reply, she won’t find out as I am sending you away to cousin Jason’s for a while. She departs, Lewis looks up, Rachel and his eyes lock, and he realizes that she heard everything. Lewis joins her, is defensive, and a confrontation erupts as he denies her criticism and then cast aspersions on her fidelity by accusing her of having an affair with Jackson. She storms into her bedroom, as he returns to his liquor.

In an unscored scene Andrew arrives at the Robards bearing instructions from Mrs. Donelson to take Rachel back to Nashville. Lewis refuses, Rachel insists and so Lewis pulls a pistol and threatens to kill Andrew. Andrew is unfazed and asks Rachel to pack. As she does, Lewis is distracted and Andrew pummels him unconscious. They depart and we flow into “Indians”, which reveals Andrew escorting Rachel through Indian country. Newman sow a lurking menace replete with drum beats, joined by a reserved Andrew’s Theme. Rachel believes the injured Lewis will not follow, but Andrew says that is not what worries him. At 0:30 a propulsive, galloping rendering of his theme caries their now galloping ride through the forest. At 0:39 a diminuendo supports a rest stop. Andrew heads up a hill to survey what lies on the other side, portentous woodwinds and soft drum strikes support his climb. He reaches the crest at 1:05 and a repeating, menacing three-note motif supports him seeing a war party riding below. Ominous strings fortify the motif after a birdcall signal catches Rachel’s attention. The Indian Theme now gains prominence with a primary woodwind line buttressed by muted horns joins the now contrapuntal three-note motif. Andrew returns, alerts Rachel of the problem, arms her with a pistol, and says they ride to the rocky flats along the stream. He says they will make enough noise to sound like seven horsemen and at 2:05 trumpets resound and as they charge forth a heroic rendering of his theme propels them. He shouts and fires his pistol intending to fool the Indians and force their flight by sounding like they are a big party. At 2:33 it is nightfall and a nocturne unfolds joined by a tender rendering of Rachel’s Theme as Andrew says they should rest the night at an inn ahead. They arrive at the J. Pettibone Inn, which is full, however the owner puts Rachel on a sofa and Andrew in a bed with two other men. As they bid each other goodnight we are graced by a romantic interlude where their two themes entwine.

“At The Inn” reveals them arriving at the stockade housing the Donelson Inn carried by a tender rendering of Rachel’s Theme by woodwinds and harpsichord. Mrs. Donelson greets them and at 0:20 sumptuous strings take up the melody as mother and daughter reunite. We close at 0:45 on a noble rendering of his theme as Andrew departs for Nashville to argue a case in court. “Robards Returns” offers a poignant score highlight of great pathos. A plaintive Rachel’s Theme supports Rachel apologizing for being a burden, only to be stunned when mother advises that Lewis waits for her in the inn, having ridden all night. We descend into pathos as he apologizes, says he does love her, and that he will never do it again. At 0:59 a molto tragico statement of her theme supports as she discloses that she does not respect him, could never trust him again, and no longer loves him. He angrily says it is Andrew! She denies it, says she never wants to see him again, and walks away. At 1:32 we close with an ominous quote of Lewis’ Theme as he threatens to return with his relatives and take her by force, shedding her family’s blood, if necessary. In an unscored scene mother tries to convince Colonel Stark to take Rachel down river to her sister in Natchez, however he declines as he does not want to take responsibility given the danger of the Indians. That night mother wakes Rachel saying the Colonel had changed his mind and that you leave for Natchez at first light.

“The River Boat” reveals saying goodbye to mother and her brother William and then boarding. The boat sets off and Rachel has one last look at her family. Newman offers a pleasant musical narrative, supporting with a gentile travel motif. At 0:38 the music stops when Rachel is surprised to see Andrew at the tiller. She demands to know if mother arranged this, and he advises how fortunate that they were both bound for Natchez. Stark’s wife Peachblossom takes her into the small cabin, where the two will live during the journey. At 0:40 the Travel Motif resumes as we see Andrew tilling during rain showers. At 1:05 we are graced by tender rendering of Rachel’s Theme as she brings him up a cup of coffee and apologizes for being rude. He tells never apologize to him for anything and o return to the warmth of the cabin. The next day at 1:28 the pleasant Travel Motif supports the barges trip down river. In ambushed the women hang their underwear on deck and Peachblossom sends Rachel over to talk to Andrew. “Ambushed” reveals Rachel asking Andrew about his plans after they reach Natchez, and he saying he needs to return up river to Nashville to resume his job. The moment is shattered at 0:29 as Indians on the shore open fire with rifles. They take cover, and hunker down until the current takes them out of range. However, a fire arrow ignites a hay bundle, and Andrew is forced to toss it overboard to contain the fire. Newman supports the attack with the ferocity of the Indian Theme, which offers a horns bellicoso and woodwinds main line, which plays over contrapuntal drums and woodwinds.

“Escape And Love” reveals it is night time and Colonel Stark and Andrew arguing. Stark says he must put to shore as he cannot navigate the rapids at night, while Andrew warns that the Indians will smell them out and attack. Stark prevails and the barge ties up on shore. Andrew decides to stand lookout on shore and that they should cut the anchor rope and drift away at the first sound of gunfire. Stark and his slave stand watch, while Rachel, who is too nervous to sleep, decides to sit on deck. Music enters with a foreboding narrative of tension, shattered at 0:13 by gunfire. Rachel takes the axe from the slave and refuses to cut the rope until Andrew is safely aboard. An ominous Indian Theme swells on strident, dissonant horns and drums of war, joined by a flight motif as Andrew runs for his life back to the barge. He is tripped by and Indian whom he kills, while on the barge Stark shoots an Indian climbing aboard to kill Rachel. At 0:56 drums usher in Andrews bold theme as he regains the barge. Rachel cuts the rope and Andrew is furious that she delayed cutting it. His theme slows and diminishes as he demands to know why she did not follow orders. His shouting, provokes her defiant rage and he breaks up with laughter from her spirit. At 1:31 his laughter diffuses the tension and her warm, and now loving theme joins as he asks why she did it? To which she answers, I was showing off and like to graze danger. He lays her down and they join in a passionate kissing embrace. At 2:05 narrative script displays “Natchez”, the capital of Spanish territory in Tennessee. Newman drapes the setting with Spanish auras and rhythms. We shift to musical gentility as we see her aunt and uncle taking her and Andrew by carriage to their house. They have declared a ball on Tuesday to celebrate their arrival, and will provided suitable attire, which delights both of them.

“German Dance” reveals Rachel in a resplendent gown dancing with Andrew to the graceful and elegant German Dance No. 1 in C Major (1790) by Ludwig van Beethoven. They are happy and eventually flow outside into the garden terrace. We segue into “Marriage Proposal”, a molto romantico score highlight. Andrew fervently confesses his undying love for Rachel, suggesting they get an annulment from the Spanish Government, with the caveat that their marriage would only be legal in Spanish territory, so they could never leave. She does not wish to restrict his career and so argues to seek a petition of divorce from Lewis. He says that would be futile, and does not want to wait. She however insists, and he storms off in anger saying it may take years before I return, with she adding, or not at all. Newman offers one of the score’s finest moments with their Love Theme borne by the renown ‘Newman Strings’ expressing exquisite romanticism. The theme’s testament to love however dissipates when Andrew’s legendary temper flares and he storms off.

“Adultery” reveals Andrew receiving a letter from John announcing that Lewis has gotten a divorce. Newman propels his run to Rachel like an arrow shot from Eros’ bow. He is ecstatic and the Love Theme blossoms, embellished by a contrapuntal string line, as he declares that they can be married immediately. He says that John informs him in this letter that Lewis obtained a divorce decree. Yet at 0:48 the music darkens and her theme shifts to melancholia as he refuses her request to read the letter. She senses a problem and insists that he disclose the grounds for divorce. He says it is not important, she persists, and he relents, saying that the grounds were adultery with me. He tries to console her, but she responds by saying you are a man and cannot begin to think how this reflects on her as a woman. He takes her into his arms and says forget the past, and let us begin a new life together in the present. At 1:42 we shift to their wedding where Newman offers a promenade felice as Colonel Stuart escorts Rachel down the aisle to Andrew. Rachel’s narration reveals that for while time had no meaning. At 1:56 the stroll together outside their farm in Natchez with Newman espousing contentment and happiness. The music shifts at 2:01 to a playful trotting motif as foal runs to its mother. Andrew promises to build her a six-column house like the one in front of them, and she counters, yes, only to have Andrew reply, let’s build our house in Nashville. At 2:15 Rachel’s Theme is offered warmth and idyllicness replete with harpsichord as her narration speaks of her happy life and house, with ‘six columns’ (actually six wood posts).

In an unscored scene, Rachel frets that after two years they have no children. Andrew reassures her as John arrives with bad news and an apology; He declares that he had been terribly mistaken, as informs them that Lewis had only petitioned for a divorce without actually obtaining one. Now, armed with knowledge of your marriage, he has divorced Rachel legally on grounds of adultery. In “The Second Marriage”, after Jon departs, Rachel begs Andrew to marry her again, but he resists angrily, asserting that holding another marriage ceremony will be an admission that they were in the wrong. She persists, begging him for her sake, for their children’s sake, and because he loves her. Andrew relents, saying he does so not because it is right, but because he loves her. Newman supports with forlorn woodwinds and pleading strings, which fully evoke the pathos of their circumstances. They hold a private ceremony at Mother Donelson’s house with a close circle of family and friends, which is unscored. In a subsequent unscored scene, on the way home they stop in town at Clark’s General Store where Lewis’ cousin Jason makes a crude remark about Rachel. Andrew becomes enraged and pummels him to near death in a fist fight. He returns bloodied to the carriage and whips the horses for a charging departure from town.

“The Passing Of Judge Hutton” reveals Andrew and Rachel stopping after they encounter a group of men off road. They are informed that a Creek ambushed killed this man and took his horse, adding that they also burned down the Henderson place. Music enters on cello triste evoking the pathos of loss with these revelations and transforms into an aching lamentation borne by Rachel’s Theme when they turn over the body and discover it is her brother William. The shifting of the melodic line among strings and woodwinds offers exquisite tear evoking music, another testament to Newman’s brilliance. Andrew tells the men it is time to mobilize the militia as it is clear that the Creeks are determined to wipe us out. At 1:00 we shift to a proud and forthright declaration of Andrew’s Theme as he leads the militia’s march down Main Street past cheering crowds. Narration by Rachel informs us that this will be the first and most difficult of the many separations that follow.

“The Seasons” reveals the passing of the seasons with a montage of Rachel and her slave Moll working the fields alone for a year and a half. Newman supports with a gorgeous pastorale, shifting at 0:31 to a bleak narrative led by a trumpet solitari as winter snows descend on the farm. At 0:50 the pastorale returns borne by strings as Spring tilling and planting unfolds. At 1:18 a spirited Andrew’s Theme supports the arrival of Jacob with news. He informs Rachel that The Indian War is over, that her husband is a hero, and that he will soon arrive. Rachel who is dirty, sweaty and unkempt from plowing the fields yells “Oh! Oh!” and runs frantically carried by her theme rendered as a flight motif to the house to make herself presentable. She spills water, knocks over the water pitcher and at 2:03 strings full of longing bring Andrew to her. We shift to the Love Theme embellished with a solo violin d’amore as she tries to explain, but his repeated passionate kisses silence her as she joins in his embrace. At 2:41 we shift to Rachel’s melody carried by solo flute delicato with harp adornment as Andrew runs outside, he pulls a baby from his saddle bag and presents it to Rachel as the son they always wanted. The music beginning at 3:05 was dialed out of the film, which is a shame as Newman’s evocative writing is superb. It offers Lincoya’s Theme borne by a gentle flute narrative with soft drums and subtle Indian auras as Andrew relates that the boy’s parents were killed and since his tribe was going to kill him, he decided to bring him home. They agree to keep his Creek name Lincoya (the abandoned one).

In an unscored scene, after Rachel puts Lincoya to sleep, Andrew drops a bombshell; to finance the war and pay the men he sold their farm and lands. She is shocked, but his calmness and self-confidence reassure her when he says he bought a house for them in Nashville, with it implied that was a reward for him winning the Indian War. “The Hermitage” opens with Rachel’s narration relating that Andrew built as promised a grand six-columned house, which they named “The Hermitage”. Sadly, she adds that he rarely resided their due to fighting wars on the battlefield or in the Senate chamber. Newman supports with a warm and stately musical narrative, which sours at 0:32 when her invitation to join the ladies of Nashville Culture Club is withdrawn last minute with the implicit message that it was due to her past adultery. Though wounded, the Hermitage melody again brightens as she relates that she would avoid social engagements, instead focusing on making the Hermitage their dream house, and safe retreat from the world.

“Death And Burial Of Lincoya” offers a score highlight of heartbreaking pathos. Rachel arrives home and is informed by Moll that Lincoya has fallen ill and she called in a doctor. She fears the worst, runs upstairs, and finds the doctor exiting the room. She tries to enter, he shakes his head not to, and she collapses into his arms sobbing. Newman offers a Pathetique with a molto tragico rendering of Rachel’s Theme to express her devastation and anguish. At 1:01 we shift to the gravesite and where once again Newman provides an evocative narrative of despair. We open with Lincoya’s Theme carried by flute triste, soft drum strikes, and strummed harp. Rachel turns to Moll and asks: “What wrong have I done that I should be punished? Am I really an evil woman? My husband is persecuted because of me. God denies me children of my own, and takes away the child I was given”.

Moll consoles her and at 1:59 we return warmly to the Hermitage carried by its theme as Rachel relates that Andrew had returned, and that she had invited his friends to celebrate the occasion. She adds that all the men accepted and came, but none of their wives. She discovers from the conversation that Andrew has bet $5,000 on the next horse race, which greatly exceeds their assets. He is confident of winning, and says if he loses his credit as Senator of Tennessee is good.

“The Race Track” reveals the Nashville elite all converging on the race track. Newman animates the scene with a festive and folksy musical narrative full of excitement. The music ends when the women who have spurned Rachel arrive, comment on how their horse will defeat Andrew’s. Rachel responds with a wager; her horses and carriage against Mrs. Pharris’s. She agrees and each party turns away from the other. The Master of Ceremony announces a race between Mr. Jacobson on Greyhound vs Mr. Jackson on Truxton for one turn around the track. They race neck to neck with Jackson bolting into the lead at the final stretch. He is declared the winner, and Mrs. Pharris says she will have the carriage delivered in the morning. Rachel shames her by saying she made the wager in anger and asks that she relieve her of it. She lowers her head and agrees as Rachel runs to congratulate Andrew. John arrives with news the Jackson had been assigned to the post of General of the Tennessee militia. The crowd applauds, but Charles Dickerson declares Jackson is indeed daring, having captured another man’s wife. Rachel asks to leave and Andrew escorts her part way, asking her to return home while he attends to matter of personal honor. She begs him, but he is resolute and leaves her.

The Duel” offers a masterpiece cue, and one of the finest in Newman’s canon. Back home he opens his dueling case to reveal two vintage pistols. Newman sow a grim music musical narrative with a dark iteration of Andrew’s Theme. He says his honor has been challenged and to command, his men must respect him. At 1:02 Rachel entreats him to not duel, with a pleading rendering of her theme. However, he is resolute and says he will journey to Kentucky in the morning as dueling remains legal there. At 1:22 she declares “Andrew. If I am to be the cause of all your quarrels, for the rest of your life, then you give me no choice… I must leave you. I will not let you be killed because of me. Nor will I let you take another man’s life. I must leave you”.

He is stunned and asks, “You would leave me?” To which she says no, and begins crying, again pleading for him to not do this. Newman supports Rachel’s final effort to dissuade him with a breath-taking crescendo appassionato, which culminates in despair at 1:56 when he again declares that he has failed her many times in his life, hopes that she be able to forgive him, and that he cannot live without honor. He takes her hand, and says, let’s go to bed. Later, as she lay awake in bed dreading the arrival of dawn, Newman supports with her theme rendered with dread and despair, replete with portentous tolling bells of doom.

Rachel, who does not sleep the whole night, dutifully wakes Andrew up at 4 am. “After The Duel” reveals her seeing him out the door, and saying, to come back to her as quickly as he can. Newman sows a bleak narrative of impending doom as she contemplates the unthinkable – that he will never return. She advises Moll that she will be working in the fields today. A montage of her performing hard physical labor unfolds supported by a tortured musical narrative empowered by her theme. At 0:56 it is night and Rachel is making candles and refuses to go to bed. Her forlorn theme unfolds atop a grim clock motif. At 1:28 a crescendo di agonia supports her collapsing into Moll’s arms weeping, as she says if he was going to come home, he would have been here by sundown. At 1:39 they hear a carriage arrive, and the crescendo shifts to one of desperation as Rachel runs out to greet it. We crest at 1:46 with joy as she sees he is alive, but it is fleeting, dissipating into fear as he has been wounded and collapses. The doctor says the shot racked his breastbone and broke some ribs. He adds that he should have been treated immediately, but stubbornly insisted to return home at once. When he recovers, he promises to raise her to the heights that no man can raise his voice against her.

“The Battle Of New Orleans” opens with martial trumpets bellicoso empowering a war-like musical narrative as a canon fires, “1812” is displayed, and the newspaper headline reads “British Burn White House”. At 0:09 a proud, bravado rendering of Andrew’s Theme supports him as general, leading an armed column of militia in a parade march down Main Street Nashville. A montage of battles unfolds empowered by his theme. At 0:26 we shift to Andrew’s command tent where he writes Rachel expressing his regret that duty takes him away from her, that he takes solace recalling the peace of the Hermitage, and the happy times when they were together. Newman supports with Rachel’s Theme expressing the loneliness of separation. Her melody is sustained as we see a montage of scenes showing Rachel struggling with the harvest and rainstorms, which turn the roads muddy and impassable. He closes saying when the war is soon finished that he will return and raise her to the heights he promised. He signs it December 10, 1814. At 1:37 we shift to the battlefield atop trumpets militari, which propel a martial musical narrative buttressed by field drums as the battle of New Orleans unfolds. Rachel’s comments offer a testament to one of the greatest victories in American history as the British army is defeated, suffering 8,000 casualties with Jackson losing only six. At 2:04 a warm and folksy rendering of the Hermitage Theme supports Rachel’s happiness of a year together, yet we close with foreboding as Andrew throws a letter into the hearth fire. Rachel joins and he angrily declares I will not do it, saying I have had enough of politics and soldiering. She asks what is up, and he says the Governor wishes to appoint him Senator, but he is angry, saying he refuses to leave he Hermitage, and storms out leaving Rachel alone bearing a wry smile.

“Rachel’s Letter” reveals Rachel’s narration voicing what she believed was Andrew’s inevitable return to Washington for what he promised would be only a year or so, which stretched into four or five, and then, more and more. We see sadness and resignation in her eyes, hear it in her voice, and her theme reflects this as it supports her narration. We shift to her writing a letter with narration, which begins with October 6, 1825. A soft and loving rendering of her theme expresses contentment that he has learned to control his temper and that he will soon be ending his political career where she looks forward to enjoying the summer with him at the Hermitage. The film however offers juxtaposition and irony as we see him beating a fellow senator with his cane, and then being presented in his office with a banner, which reads; “Jackson For President”. In an unscored scene John counsels Andrew and Rachel that easterners will vigorously oppose a western presidential bid, and will purposely seek every means possible to provoke his temper including personal attacks on Rachel. Jackson is confident he can master his temper, yet we see John and Rachel remain unconvinced. After John leaves she gifts him a picture of her to place in his watch, a reminder to control his temper. (*) “Jackson Provoked” reveals a political rally in town supported by festive source music tunes. Rachel and Moll have snuck out of the house to hear his speech. Everything however goes awry when political operatives seeded in the crowd shout out taunts to provoke Jackson. They try to turn the crowd against him, including accusing him of; gambling, murder, being an adulterer, and lastly of his prostitute becoming First Lady. The last insult triggers Jackson’s renown temper, with his people restraining him. Rachel flees the now agitated crowd only to come upon a march with men chanting and holding a sign, which says’ “We Don’t Want a Prostitute in the White House”. She is overcome and distraught as people recognize her, and begin taunting her. “Yankee Doddle Dandy” joins as she again flees. She is almost run down by a wagon, which induces a heart attack.

“Rachel’s Illness” reveals her on her death bed with a distraught Andrew instructing the doctor to do everything possible. The next day he brings a breakfast tray and feeds her. She inquires as to whether he won, and he says to relax and regain your strength. Newman supports with Rachel’s Theme, but it is lost its vitality and we feel her life ebbing in the notes. The next day in “The Presidency” John and friends arrive to deliver great news, that he has won the election! He goes up stairs and a serene rendering of his theme supports, joined by portentous bell tolls. His theme shifts, becoming warm, and loving as he joins Rachel. He delivers the news that he won, that we are going to Washington City, as he hugs her and declares you are now First Lady. At 1:16 the Love Theme joins as she is tearful and thanks him for keeping every promise, he ever made to her. He tells her to sleep and departs at 1:42 supported by a final bell toll. At 1:43 we segue into “The Death Of Rachel” atop a repeating three-note harp motif as we see Andrew asleep downstairs by the hearth. At 1:58 Rachel senses her time is up and an agonal quote of her theme supports her yelling “Andrew!”. Strings of desperation carry Andrew’s run upstairs where he finds Rachel collapsed on the landing. He carries Rachel into the bedroom and then sits on her bed with her in his arms. Her theme, exhausted by life, ebbs as she informs him that she is glad she never left him, and that she is not going to Washington City with him after all. She succumbs, as does her theme, to death as Moll declares; “They killed her.” At 3:00 a solemn, and reverential statement of his theme supports his walk to the window, where he declares; “In the presence of this gentle soul, I can, and do forgive my enemies”. We close at 3:42 with a wistful rendering of her theme as Andrew adds; “Those vile wretches who slandered her, must look to God for mercy” as he kneels in anguish. At 4:04 we shift to Washington City where dignitaries have assembled. The clerk announces, “The President of the United States”, and Andrew exits the White House and joins the dignitaries. His proud, forthright and bravado theme has been transformed and is now rendered maestoso, with dignity, reserve, and honor by horns nobile for perhaps its most moving iteration of the score. At 4:39, a bridge by harpsichord and harp usher in a final exposition of a wistful Rachel’s Theme with interplay of a loving Andrew’s Theme as Andrew’s mind speaks; “Well, here we are Rachel. Look at them. Some of those good people feel sorry for me. Poor fools they are. They don’t know what memories I’ve brought with me”. Here we flash back and a narrated montage of their life together unfolds supported by a wistful rendering of her theme. We conclude the film with noble grandeur as “The End” displays.

I would like to thank Nick Redman for this remarkable restoration of Alfred Newman’s masterpiece, “The President’s Lady”. Newman recorded using close-up microphones for a dry, composite sound, and long-shot microphones for a more ambient sound. Each had isolated channels on the optical source, which allowed the technical team to create a stereophonic recording, that offers a wonderful listening experience. Newman saw opportunity with this assignment, which explores two very willful people, whose lives entwine in a love for the ages, but also suffer grievously, beset by malevolent people and forces beyond their control. For Andrew, Newman brought him to life by infusing heroism, self-assurance, military pageantry, and solemn nobility. For Rachel, he infused elegance, tenderness, love, and a yearning, long-suffering romanticism. These two characters, and their musical identities formed the nexus of his score, and I must say that their themes expression, interplay and multiplicity of renderings was often, breath-taking. I believe that this may be one of the most emotional scores in Newman’s canon, with wonderful set pieces and multiple crescendo appassiantos, which evoked tears and achieved sublimity. Folks, this score is a testament to Alfred Newman’s genius, and mastery of his craft. In every scene his music enhances character expression, setting and complex emotional dynamics. I believe that in the final analysis, his music ultimately transcends its film. I highly recommend you purchase this quality album, an essential for Newman lovers, and take in the film to bear witness to his handiwork.

For those of you unfamiliar with the score, I have embedded a YouTube link to a 14-minute suite: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t2q3SHNJxB4

Buy the President’s Lady soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- Main Title (1:53)

- Rachel (1:30)

- The Robards (3:07)

- Indians (4:20)

- At the Inn (0:58)

- Robards Returns (1:41)

- The River Boat (1:47)

- Ambushed (1:38)

- Escape and Love (2:47)

- German Dance (3:49)

- Marriage Proposal (2:08)

- Adultery (3:02)

- The Second Marriage (0:54)

- The Passing of Judge Hutton (1:43)

- The Seasons (3:55)

- The Hermitage (0:54)

- Death and Burial of Lincoya (2:18)

- The Race Track (0:49)

- The Duel (3:08)

- After the Duel (2:08)

- The Battle of New Orleans (2:23)

- Rachel’s Letter (1:11)

- Rachel’s Illness (1:02)

- The Presidency/The Death of Rachel (6:16)

Varese Sarabande CD Club VCL 11081088 (1953/2008)

Running Time: 55 minutes 21 seconds

Music composed and conducted by Alfred Newman. Orchestrations by Edward B. Powell, Bernard Mayers and Herbert W. Spencer. Recorded and mixed by XXXX. Score produced by Alfred Newman. Album produced by Nick Redman and Robert Townson.