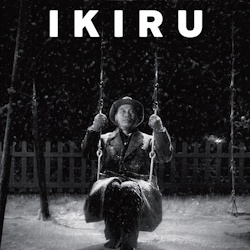

IKIRU – Fumio Hayasaka

GREATEST SCORES OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

GREATEST SCORES OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Original Review by Craig Lysy

Screenwriter Hideo Oguni was approached by director Akira Kurosawa for his next project, which was to be inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s acclaimed novella “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” about a man diagnosed with terminal disease who seeks solace for the short time he has left to live. This resulting film, Ikiru, inaugurated a renowned collaboration between screenwriter Oguni and Kurosawa, which would go on to encompass many of the finest films in Japanese cinema, including Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958), Sanjuro (1962), High and Low (1963), Dodes’ka-den (1970), and Ran (1985). Toho Company agreed to finance the project and assigned production to Sōjirō Motoki. Kurosawa would direct, and the final screenplay was credited to Oguni, Kurosawa, and Shinobu Hashimoto. A fine cast was assembled, which included Takashi Shimura as Kanji Watanabe, Shinichi Himori as Kimura, and Haruo Tanaka as Sakai.

The film offers a story of a man facing imminent death, who seeks in his final days solace in a quest for the meaning of life. Kanji Watanabe is a listless bureaucrat who gains inspiration and is transformed when he rediscovers joy from a young female subordinate. He returns to work after an extended medical leave with uncharacteristic passion and decides that his legacy will be to build a playground for children so they may play and have fun. The film was a commercial success, and received universal praise. Today it is considered a Kurosawa masterpiece and one of the greatest films of all time. The film received no Academy Award nominations, although interestingly the 2022 English-language remake of the film, Living, did receive Oscar nominations for screenwriter Kazuo Ishiguro and lead actor Bill Nighy.

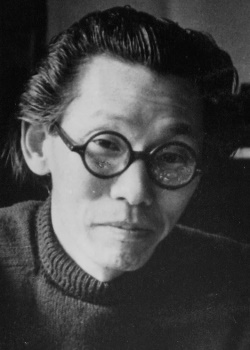

Composer Fumio Hayasaka was director Akira Kurosawa’s composer of choice. They had a fruitful collaboration of five previous films, which included “Drunken Angel” (1948), “Stray Dog” (1949), “Scandal” (1950), “Rashomon” (1950), and “The Idiot” (1951). The two decided to spot music in the film judiciously, often using silence, for which Kurosawa was renowned, and character dialogue to carry many of the scenes. Indeed, the score clocks in at just over twenty-three minutes. As was characteristic of Hayasaka’s scoring methodology, his music generally voices the scene’s emotional dynamics, speaking directly to the feelings, both expressed, and withheld by the characters.

Composer Fumio Hayasaka was director Akira Kurosawa’s composer of choice. They had a fruitful collaboration of five previous films, which included “Drunken Angel” (1948), “Stray Dog” (1949), “Scandal” (1950), “Rashomon” (1950), and “The Idiot” (1951). The two decided to spot music in the film judiciously, often using silence, for which Kurosawa was renowned, and character dialogue to carry many of the scenes. Indeed, the score clocks in at just over twenty-three minutes. As was characteristic of Hayasaka’s scoring methodology, his music generally voices the scene’s emotional dynamics, speaking directly to the feelings, both expressed, and withheld by the characters.

In fashioning his soundscape, I believe Hayasaka understood that Ikiru explored the efforts of a man who faces his mortality with the painful realization that he in the end, wasted his life. This realization is made manifest in the haunting lyrics and melody of the 1915 song “Gondola No Uta” by Isamu Yoshii and Shinpei Nakayama. The song’s lyrics offer the counsel of a wise elder to younger souls. It cautions against missing the opportunities afforded young people when they are available, as they are often fleeting and pass with regret, unrealized with growing age. In a masterstroke of conception, Hayasaka uses the song as an idée fix, which grounds the film’s storytelling. How he transforms it into a paean of joy celebrating Kanji’s legacy at the film’s end, was poetic. Two other themes are notable; the Regret Theme, offers a Pathetique, a musical narrative of remorse, and regret, speaking to Kanji’s realization that he has squandered God’s precious gift of life. It offers a forlorn meandering oboe lacking purpose attended by a retinue of mid register woodwinds and horns, joined in a danza dell delusione. Regretfully Kurosawa dialed out this theme, replacing it with distant train horns – an allusion of time’s unrelenting march forward. Having watched the scene with both versions, I believe Hayasaka’s conception worked better. Lastly, we have the Happiness Theme, embodied by Toyo, the young woman whose youth, and joy of living served to catalyze Kanji’s transformation. It offers a youthful, spritely tune rendered as a danza felice.

Hayasaka also infused his score with a number of contemporaneous tunes and classics to provide the requisite cultural authenticity, including; “J’ai Deux Amours” by Vincent Scotto, Georges Koger and Henri Varna, “Come On-A My House” by William Saroyan and Ross Bagdasarian, “Cuban Mambo” by Xavier Cugat and Rafael Angulo, “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” by Al Hoffman, Mack David, and Jerry Livingston, and “Too Young” by Sidney Lippman and Sylvia Dee, plus classical excerpts fpom “Parade of the Tin Soldiers” by Leon Jessel, and “Les Patineurs” (The Skater’s Waltz) Op. 183 by Émile Waldteufel.

“Titles” offers a score highlight where Hayasaka juxtaposes restlessness and foreboding with tenderness to portent the coming drama. It opens with trumpets and antiphonal horns dramatico as the Toho company logo displays. At 0:26 we decrescendo into tranquility as the film title displays and the roll of the opening credits commence as white script against a black background. A tender musical narrative, full of sentimentality unfolds. Yet at 1:15 the warring antiphonal fanfare that opened the film resurges sowing unease. A decrescendo at 1:49 with flowing harp glissandi tresses brings the opening credits to a close. We enter the film proper with narration over an x-ray, which announces the presence of stomach cancer, which at this time unknown to the patient. We see Kanji Watanabe, Public Affairs Section Chief reviewing and signing paperwork at his desk. Narration informs us of a life lacking joy or happiness, a life wasted, which none will remember when he passes.

“Petition Gets The Runaround” reveals a group of parents attempting to petition Section Head Watanabe to clean up an overflowing cesspool and replace it with a children’s play park. Kanji, true to form, uses bureaucratic runaround to foil and frustrate change as the screen painfully displays one department after another where parents are confounded and advised that they came to the wrong department; Sanitation, District Health Center, Environmental Sanitation, Preventive Sanitation, Disease Control, Pest Control, Sewage Department, City Planning, Zoning, City Councilman, Mayor, Public Affairs, and Public Works. Hayasaka supports with a plodding bassoon led musical narrative of tedium ad nauseum, which never resolves to speak to the parent’s frustrated efforts. The mothers finally explode in anger at the Public Works officer for giving them the runaround. In unscored scenes, subordinates are surprised as their boss (Kanji) has taken a day off, something he has never done before. They wonder who will replace him as he has been ill of late. At hospital, Kanji exits the x-ray room and takes a seat in the waiting room.

“Waiting Room Foreboding” reveals another patient stating that doctors tell patients that all they have is a mild ulcer, but then he begins listing the symptoms of stomach cancer; dull pain, burping, dry tongue, vomiting, always thirsty, and black stools. A look of terror descends upon Kanji as a dire, pulsing low register woodwinds and horns emote a musical narrative of impending doom, which commences after the mention of black stools. “Diagnosis” reveals Kanji meeting with a physician, his intern and two nurses. He tells Kanji that it is just a mild ulcer, which can be treated by diet. Kanji reacts with disbelief asking if he can operate. The doctor says it can be treated medically. Hayasaka sustains the dirge-like musical narrative of the previous cue to support the scene. After he departs, the doctor informs his intern that the man has six months at best. Kanji walks the streets resigned to death engulfed in silence. As he turns a corner, the loud noise of busy vehicle traffic explodes to shatter the silence and awake him to the real world.

In unscored scenes Mitsuo, Kanji’s son and his wife complain of living in Kanji’s old house. Shamelessly they express desire to use his retirement and pension money to buy a new one of their own. They joke that even he does not want to take that much money to the grave. As they turn on a light, they are shocked to discover Kanji sitting in the dark. The son and his wife are mortified as a distraught Kanji departs seeking escape from his misery. In “Memory 1” a contemplative Kanji sits trance-like with his sake, beset by regret. Hayasaka introduces the Regret Theme, a Pathetique which offers a musical narrative of remorse, and regret, speaking to Kanji’s realization that he has squandered God’s precious gift of life. It offers a forlorn meandering oboe lacking purpose, attended by a retinue of mid register woodwinds and horns, joined in a danza dell delusione. The following four tracks, “Memory 2 – 5” all reprise the theme with slight variations of form and length, each perfectly speaking the words Kanji cannot utter. Yet in the film, Kurosawa replaces these “memory” cues with distant train whistles. An allusion that life has left him behind? I the final analysis, having repeatedly watched the scene, I prefer Hayasaka’s original conception.

Kanji acquaints with an eccentric novelist, gifting him some of his medicine given that the pharmacy is closed. The novelist is grateful, but Kanji refuses recompense, disclosing he is dying of stomach cancer. The two men bond, and when Kanji discloses that he has 5,000 yen to spend, he accepts the man’s offer to enjoy the pleasures of life as God intended by joining him as they set off to take in the pleasures of Tokyo night life. On the way they stop of at a game gallery and he convinces Kanji to play Pachinko saying the silver balls represent your life. Adding, people strangle themselves in their daily lives, and that Pachinko sets them free. “Life’s Ball” offers refulgent twinkling wonderment as Kanji plays Pachinko and wins. (*) “Saloon” reveals that as they navigate a crowed and festive saloon, animated source music supports providing the requisite ambiance. Kanji is buffeted by the raucous crowd and has his hat stolen by a bar woman. The novelist coaxes him to push on saying he is a new man now. Kanji agrees and buys a new hat – a metaphor for rebirth. They enter the main bar, order some drinks, and converse with the owner’s wife as Josephine Baker sings a classic French song of a man who is torn, being both home sick and love sick.

Soon they head up the stairs to see the show carried by slow dance rhythms. Kanji gawks in astonishment as they move through a sea of couples locked in amorous embraces. As they wade through the crowd a pianist plays an energetic Swing tune. Kanji watches with amazement as women dance around him, one of which takes a liking to him, and sits on his lap. The piano player asks if anyone has a favorite song, they would like him to play and Kanji asks “Life is Short”. The piano player is confused until Kanji sings the line “Fall in Love maidens”, to which he responds, ah, the love song! In Gondola Song Café”, as the piano player sits, we see strands of beads swaying, a metaphor of a pendulum marking the passage of time. As the ballad unfolds, Kanji provides the vocals, yet they abound with sadness and regret, evoking his tears.

Afterwards, the Novelist says, that’s it, and drags him away to watch the strip show. As a woman dances seductively and disrobes Kanji becomes aroused and departs. Supported by “Strip Show”, Hayasaka provides an exotic drum empowered rhythm with pizzicato bass. In (*) “Fleeing the Club” Kanji flees and the Novelist pursues through throngs of people and the traffic chaos he causes. The song “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” sung by Dinah Shore animates the scene. (*) “Latin Club” reveals a new crowded nightclub, Hayasaka sets the festive ambiance with the trumpets, and bongo drum propelled Latin rhythms of the song “Cuban Mambo performed by Xavier Cugat and Three Beaus and a Peep. Both Kanji, and the Novelist have paired off with women and dancing cheek to cheek on the overcrowded dance floor. (*) “Taxi Ride” reveals the men have left with their dance partners in a taxi. Kanji orders the taxi to stop, and he gets out to vomit. Juxtaposed is the musical narrative, which offers the happy and welcoming song “Come On-A My House”, wafting in from the background. As Kanji returns, the two women decide to sing the song themselves.

Kanji and the Novelist both grimace at the off-key performance, and we see in Kanji’s expression, that the hedonist night life is not the solution he is seeking. The next day reveals a trance-like Kanji walking the bustling streets. Toyo, his young female subordinate greets him and advises that she has quit to take up a new job, which brings her happiness – making toys. She needs him to formalize her resignation with his official stamp, and he invites her to his home. Back home Mitsuo and his wife continue to argue over the inheritance only to be surprised when Kanji arrives with a young woman. She sees his award for thirty years of services, but is saddened when he reveals that he remembers no accomplishments, only tedium and that he was bored. He notarizes the document and asks that she take his sick leave form to work. As she departs, Kanji decides to escort her and Mitsuo watches from the second floor as Toyo tenderly adjusts his coat.

As they walk in “Watanabe & Toyo” her youthful optimistic spirit makes Kanji smile and Hayasaka supports with the Happiness Theme, a playful, youthful, theme, full of wonderment, which emotes as a danza infantile with a music box sensibility. (*) “Lunch” reveals the two dining at a café. A playful tune set a pleasant ambiance as they enjoy their time together, and she shares her unflattering nicknames she has given her coworkers, eliciting Kanji’s laughter and amusement. In (*) “An Afternoon of Merriment”, after lunch he asks her to delay her resignation until tomorrow as he is enjoying his time with her. She consents and they have fun at the Pachinko gallery. Next, they go roller skating, which is supported by the elegant Waldteufel’s “Les Patineurs” (The Skater’s Waltz). From there they go to an amusement park and carnivalesque music plays while she eats ice cream as a merry-go-round spins in the background. From there they go to a movie theater where he dozes as a violin propelled danza spiritoso makes Toyo laugh. At dinner she remarks that he looks tired, but he asserts he had a wonderful afternoon. Yet regret resurfaces as he relates that she was right when she joked at work that he worked like a mummy. Sadly, he adds that he did it for his son’s sake after his mother died, but now he sees that he does not appreciate his sacrifice.

In “Heading Home” she relates that even though he bad mouthed his son, she can tell that he still loves him dearly, which elicits a smile, buttressed by a reprise of the dance-like rhythms of the Regret Theme. The theme carries his walk home, ending as he sips tea while his son reads the newspaper and his wife knits. Reduced to talking about the weather, Kanji decides to reveal his situation. As he tries to speak his son interrupts and castigates him for his debauchery with the young woman, and insists that loose ends regarding their inheritance must be addressed. As the son continues to castigate Kanji in “Outstanding Man’s Impatience” shrill strings of pain descend and crash at 0:09 in devastation as he realizes that he is of no importance to his family, who only desire his inheritance. He leaves them in despair, without uttering a word, descending into the black depths of the first floor. In “Vacancy at the Seat of the Citizen’s Section Chief” a repeating five-note motif, which never resolves unfolds, consisting of a drum strike, wailing woodwinds of woe, and pizzicato string textures that support narration regarding staff concern over their boss’ absence. In a scene change, Kanji tries to elicit Toyo to spend another day with him, but she angrily rejects him saying she needs to work to make money and has no time for this. She says I am ending this now, walks inside and slams the door. As he leaves with despondency, she runs out, smiles, and says, ok, tonight is the last time.

“Something Happened to Me” reveals the two dining with sumptuous strings voicing the melody to the “Happy Birthday” song, yet there is no celebratory joy or happiness to be found, only profound sadness. In (*) “Nothing Left To Talk About”, as Kanji sits with his head bowed, Toyo looks around the restaurant and see a festive party to her right, and a couple in love snuggling to her left. Hayasaka offers a bright danza felice in juxtaposition. A birthday cake is brought out to the birthday party crowd. When he asks that they go for a stroll, she says she would rather go to the sweet shop, and then the noodle shop. She then asks; “What is the point of all of this, since we have run out of things to talk about?” She adds that she feels bad saying this, since he pays for everything Now frustrated she says she has had enough. When he lifts his eyes, filled with sadness, she wounds him saying; “There is that face again. You give me the creeps”. She says she is not into a May – December romance, and insists that he say what he wants. (*) “The Revelation” reveals that after an uncomfortable pause, he raises his head and looks her in the eyes. Once again Hayasaka juxtaposes the sadness of the moment offering the playful, child-like march “Parade of the Tin Soldiers” (1897) by Leon Jessel for the party goers, as he says to her, that he does not have much time left as he is dying of stomach cancer. With bitterness he adds that his son has abandoned him, as did his parents and that he is all alone. When she asks why me? He points to his heart and says that she gives him a warm feeling here. He then moves closer and asks what makes her so lively, so full of life, as this is why this old mummy envies you. He says, he wants to feel this way just once before he dies. She pulls out a windup toy rabbit and says that she makes things like this for fun, but also because they make other people happy. The music crescendos to support a long pause as we see the gears in Kanji’s mind churning juxtaposed with Toyo’s facial discomfort. He has an epiphany, his eyes brighten, and he turns to her and says, it is not too late. He runs out holding the toy rabbit saying that there is something he can do as the young party goers wish a young woman well, happily singing “Happy Birthday”, while a contemplative Toyo gazes down in silence.

(*) “Kanji Reborn” reveals the next day Kanji’s staff returning to work and saying that it is only a matter of time before he resigns. They are shocked to find his new hat hung on the coat rack and him working. He orders his staff to proceed with cleaning up the cesspool by assigning it to Public Works. Hayasaka alludes to his epiphany last night by reprising a tender rendering of the “Happy Birthday” melody. For most of the remaining third of the film, Hayasaka withheld music, believing the character dialogue and storytelling should carry the scenes. Five months later, narration supports a funeral display of Kanji’s portrait surrounded by flowers, and draped in Japanese tradition with a black ribbon, as family and friends partake in the wake meal beneath the altar. Parents arrive outside and insist on speaking to the Deputy Mayor. An uncomfortable conversation unfolds as they accuse the Deputy Mayor, who is soon running for Mayor of taking credit for the park as a campaign tactic and not even mentioning Mr. Watanabe in his speech opening the park. They believe his passing during the Park’s opening ceremony was an act of grievance. He dismisses their claims saying he died of internal hemorrhage due to stomach cancer. He then returns to the wake, only to be greeted by the stony silence of all in attendance.

Inside the Deputy mayor gives some acknowledgement of Watanabe’s effort, but refuses to say he was ultimately responsible for the park’s creation. His defensive speech is interrupted by the parents from the Park’s district who wish to burn incense for the deceased. The mothers enter sobbing and kneel respectfully before his altar. They bestow gifts and wail, which begins to have an effect on the family and officials. As the mothers, priests, and other women depart the ceremony in tears, a heavy pall of silence drapes the men remaining as the camera fixates on Kanji’s portrait. After the weeping women of the funeral assembly return, the deputy mayor, and other city councilmen bow to the family, then to Watanabe’s altar, and then depart. With blatant pettiness, the various city department heads then begin asserting their role in creating the park, refuting the claim that Watanabe should receive sole credit. They then all admit their perplexity as to how he could change so radically with some attributing it to cancer, some to his manhood being rejuvenated by his affair with Toyo.

We flashback with Kanji departing work and demanding that his subordinates do whatever it takes to build the park. In a scene shift Kanji and his subordinates overlook the cesspool site in a driving rainstorm, where he wades through its muddy waters it to the amazement of all. We return to the Wake where they credit his enthusiasm and abandoning tradition by challenging other directors on their own turf. They assert that his tenacity overcame all opposition, as well as the bureaucracy’s inertia. I another flashback, Kanji enters the Deputy Mayor’s office backed by a contingent of mothers. The Deputy Mayor says it is best to let the project die, but Kanji persists, doing the unthinkable, defying his superior and daring to ask him to reconsider. They all could see that the project was the only thing keeping him alive. He even defied a mob boss who wanted to instead create a red-light district. In the end, the Deputy Mayor gave the project a green light to proceed. Kanji watched the construction, like a father waiting for the birth of his child. Back at the Wake, the sake has facilitated the truthfulness of drunks as they admit Watanabe’s tenacious drive, and their complicity in perpetuating a bureaucracy that opposes change, progress and addressing the needs of the people.

A woman interrupts and brings in Kanji’s soiled top hat and says the policeman that found it would like to honor him by burning incense. Mitsuo holds the hat and the room descends into silence as the man pays his respects. As he departs, he accepts the offer of sake. He then relates that while on patrol he came across Mr. Watanabe swinging on a swing as it snowed. He said he thought he was drunk, and just let him be. He now regrets that failing to take him in contributed to his death, but adds that he seemed so happy as he sang a song of his life with a haunting voice, which filled the depths of my soul. “Gondola Song” reveals a flashback to a contented Kanji swinging to and fro on a swing. He has reclaimed his life and left a legacy, which allows him to die in peace. As he swings, he sings in a haunting voice the first stanza of the Gondola song. At this point we return to his portrait and then the Wake as he sings the last two lines.

Mitsuo and his wife depart with the hat and he relates to her that Kanji left a bag under the stairs with his name on it, which contained his handbook, seal and forms claiming his retirement bonus. He adds it was cruel of him not to disclose he had cancer. Back in the Wake room the men declare that Kanji’s death must not be forgotten and that they as reborn men must carry on his legacy – sacrificing ourselves in service of the people. The next day Ono, the new Section Head sits at Kanji’s desk stamping his seal on forms. A subordinate brings a complaint of a sewer link, and Ono says refer the people to Public Works. At this point subordinate Kimura rises in outrage, his angry expression offering a scathing rebuke at Ono’s betrayal of Watanabe’s legacy. He dejectedly sits back down, and bows his head, disappearing behind a pile of paperwork. Later, we shift to him looking down from an overpass at site of happy children playing in Kanji’s Park. We flow into “Ending” as a transformed Gondola Theme unfolds with joy and the hope of brighter days ahead as we watch happy children playing. The film closes at 0:43 with the theme blossoming grandly with fulfillment as Kimura walks away.

The score’s audio is uneven with some cues archival (#11), and some apparently remastered, but on balance I am thankful for the album. I believe Fumio Hayasaka had an intuitive understanding of Kurosawa psyche, similar to Bernard Herrmann’s insight into Alfred Hitchcock’s. In a masterstroke of conception, he established an idée fix using the “Gondola no Uta” song to ground his musical narrative. The song, filled with wisdom warning of the regret of missed opportunities, informs us of Kanji’s wasted life. Yet once Kanji experiences an epiphany, both he, and the song are ultimately transformed – the power of redemption manifest. I believe Hayasaka once again revealed his genius with this score, using nuance, minimalism, and thematic transformation to elevate the film in every way, thus ensuring that Kurosawa achieved his vision. Indeed, the confluence of music, acting and storytelling during the film’s crucial scenes was often evocative, poignant, and profound. Folks, I highly recommend this score and film as one of the finest in Japanese cinema, and if you can find and purchase the six CD Kurosawa Film Music Collection box set, buy it, as it offers one of the most brilliant director-composer collaborations in history.

The score’s audio is uneven with some cues archival (#11), and some apparently remastered, but on balance I am thankful for the album. I believe Fumio Hayasaka had an intuitive understanding of Kurosawa psyche, similar to Bernard Herrmann’s insight into Alfred Hitchcock’s. In a masterstroke of conception, he established an idée fix using the “Gondola no Uta” song to ground his musical narrative. The song, filled with wisdom warning of the regret of missed opportunities, informs us of Kanji’s wasted life. Yet once Kanji experiences an epiphany, both he, and the song are ultimately transformed – the power of redemption manifest. I believe Hayasaka once again revealed his genius with this score, using nuance, minimalism, and thematic transformation to elevate the film in every way, thus ensuring that Kurosawa achieved his vision. Indeed, the confluence of music, acting and storytelling during the film’s crucial scenes was often evocative, poignant, and profound. Folks, I highly recommend this score and film as one of the finest in Japanese cinema, and if you can find and purchase the six CD Kurosawa Film Music Collection box set, buy it, as it offers one of the most brilliant director-composer collaborations in history.

For those of you unfamiliar with the score, I have embedded a YouTube link to Kanji singing “Gondola No Uta” – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nx5M4AkIeTE

Buy the Ikiru soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- Ikiru Titles (2:08)

- Petition Gets The Runaround (2:41)

- Waiting Room Foreboding (0:59)

- Diagnosis (1:23)

- Memory 1 (0:48)

- Memory 2 (0:37)

- Memory 3 (0:59)

- Memory 4 (0:14)

- Memory 5 (0:27)

- Life’s Ball (0:07)

- Ikiru Gondola Song Café (2:42)

- Ikiru Strip Show (1:10)

- Watanabe & Toyo (1:29)

- Heading Home (0:34)

- Outstanding Man’s Impatience (0:16)

- Vacancy At The Seat Of The Citizen’s Section Chief (1:04)

- Something Happened To Me (0:33)

- Ikiru Gondola Song (1:33)

- Ikiru Ending (1:08)

- Waiting Room Foreboding Ordinary Sound (0:47)

- Diagnosis Ordinary Sound (1:06)

- Something Happened To Me (Alternative Version) (0:34)

Toho Music Corporation AKS-1 (1952/2001)

Running Time: 23 minutes 11 seconds

Music composed and conducted by Fumio Hayasaka. Orchestrations by XXXX. Recorded and mixed by Yoshikazu Iwasaki. Score produced by Fumio Hayasaka. Album produced by Masao Iwase.