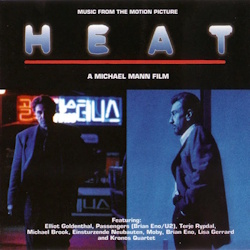

HEAT – Elliot Goldenthal

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

Widely considered one of the best action thrillers of the 1990s, and notable for marking the first time that legendary actors Robert De Niro and Al Pacino appeared together in the same scenes on screen (they were both in The Godfather Part II but did not feature in the same scenes), Heat follows the intense cat-and-mouse conflict between a meticulous professional thief and a relentless police detective in Los Angeles. De Niro plays Neil McCauley, a highly disciplined career criminal who leads a small crew of expert thieves. After a planned armored car robbery goes disastrously wrong, the gang attracts increased attention from law enforcement in the shape of Vincent Hanna (Pacino), an LAPD robbery-homicide detective. As Hanna becomes obsessively focused on tracking McCauley and his team – alienating his wife and daughter in the process – McCauley’s crew prepares for an even bigger and more dangerous bank heist, placing both men in each other’s crosshairs.

The film is directed by Michael Mann and has a stellar cast supporting De Niro and Pacino, including Val Kilmer, Jon Voight, Tom Sizemore, Diane Venora, Amy Brenneman, and Ashley Judd, many of whom give career-best performances. Mann had begun working on the script for Heat back in the late 1970s, when he was a journeyman writer working on TV cop shows like Starsky & Hutch and Police Story, prior to him directing his first film Thief in 1981, and prior to the creation of Miami Vice. Mann had been inspired by the life of a real Chicago police officer, and he first developed his script as a TV pilot, which eventually became the 1989 TV movie L.A. Takedown, before he expanded it and re-made it as the feature film we know today.

Mann is a notoriously finicky director when comes to the music in his films, and is infamous for making last-minute changes to his soundtracks, sometimes replacing entire sequences wholesale in favor of needle-drops, source music, or newly commissioned music from new composers. This happened on Thief with Tangerine Dream and Craig Safan, on Manhunter with the band The Reds and composer Michel Rubini, on The Last of the Mohicans with Randy Edelman and Trevor Jones, and on numerous recent films. Heat had a little less musical chaos, but still saw Mann blending Elliot Goldenthal’s brooding, textural score with tracks by electronic artists like Moby and Brian Eno, creating a soundscape that appropriately emphasizes the film’s themes of loneliness and urban isolation, but still results in there being a certain disconnect between the different musical aspects across the project as a whole.

Mann’s intensely hands-on approach has often created tension with composers. Fully developed dramatic cues are sometimes heavily edited, repositioned, or removed altogether in favor of licensed tracks that Mann believes better match a scene’s emotional tone. However, I have often found that him doing undermines the intended musical arcs and shift the composer’s role away from narrative storytelling toward merely providing atmospheric texture. Mann’s broader preference for mood over continuity also tends to prioritize immediacy over thematic development and, as a result, the scores in his films sometimes feel fragmented or incomplete when heard outside the film, with cues being cut short or mixed low so that their dramatic impact is blunted. Such methods can be especially frustrating when it comes to composers like Elliot Goldenthal whose music is rooted in classical symphonic traditions where sustained musical structure is essential.

Mann’s intensely hands-on approach has often created tension with composers. Fully developed dramatic cues are sometimes heavily edited, repositioned, or removed altogether in favor of licensed tracks that Mann believes better match a scene’s emotional tone. However, I have often found that him doing undermines the intended musical arcs and shift the composer’s role away from narrative storytelling toward merely providing atmospheric texture. Mann’s broader preference for mood over continuity also tends to prioritize immediacy over thematic development and, as a result, the scores in his films sometimes feel fragmented or incomplete when heard outside the film, with cues being cut short or mixed low so that their dramatic impact is blunted. Such methods can be especially frustrating when it comes to composers like Elliot Goldenthal whose music is rooted in classical symphonic traditions where sustained musical structure is essential.

Goldenthal came to Heat hot off the commercial success of films like Alien 3, Demolition Man, and Batman Forever, as well as his Oscar nomination for Interview with the Vampire in 1994. In an interview with Dan Goldwasser for Soundtrack Net back in the day, Goldenthal recalls that he and Mann were going for ‘an atmospheric situation,’ and that it was the first time he had used what he called a “guitar orchestra” of six or eight guitars, all playing with different tunings, stacked up on top of each other in a musical way, in combination with mixed meter percussion. Goldenthal dubbed this the group the Deaf Elk Guitars, and it featured several rock guitarists, including Page Hamilton of the metal band Helmet, who would later go on to work with Goldenthal again on the scores for In Dreams and Titus.

This guitar-and-percussion sound dominates much of the score, although there are still several moments where Goldenthal unleashes his familiar orchestral power, to greatly satisfying results. Elsewhere, Goldenthal use of the more retrained tones of a string quartet, the Kronos Quartet, featuring David Harrington and John Sherba on violin, Hank Dutt on viola, and Joan Jeanrenaud on cello. The album contains 11 cues of Goldenthal’s score, totaling just under half an hour. There is no main recurring theme in Heat per se – likely a result of Mann’s editing process and musical tinkering – and so instead Goldenthal creates an intense atmosphere with his music that is built around specific instruments and tones rather than recognizable melodic ideas. It’s cool, it’s dramatic, it’s detached and impersonal, and it has a sense of world-weariness bordering on fatalism that I actually quite like.

The Kronos Quartet is most prominent in the opening cue “Heat,” and then later in “Refinery Surveillance” and “Predator Diorama,” although in each of them Goldenthal layers them against the guitars and the keyboard textures, and in doing so establishes the score’s overarching instrumental palette. The first part of “Heat” is mostly about shifting textures, colors, and increasingly agitated rhythmic ideas, including one idea which maybe a sampled vocal wail, which gives the whole thing a dirty, gritty sound. By the middle of the cue the music has devolved into vicious, dissonant chaos, and then by the end has become a raw, furious groove full of forward motion and swaggering masculinity. This rhythmic groove continues through much of the icily dramatic “Refinery Surveillance” in a manner than sometimes reminds me of Michael Kamen’s 1980s action scores, but then in “Predator Diorama” the sound becomes much more expansively orchestral, exploding into a sequence of anguished-sounding brassy violence that recalls some of the more vivid moments of Alien 3 and Demolition Man.

The Deaf Elk Guitars are most prominent in cues like “Condensers,” “Steel Cello Lament,” and “Run Uphill,” which together create a haunting blast of sound that has a lonely, moody, wonderfully evocative feel. It speaks to the urban landscape through which Hanna and McCauley stalk each other, and in listening to these cues I can’t help but wonder whether Goldenthal was inspired by Bernard Herrmann’s score for Taxi Driver, which was of course the film that made Robert De Niro a star. Goldenthal uses his electric guitars similarly to the way Herrmann used his saxophones, to create a cynically detached sound, a little bit jazzy, but without the warmth and expressiveness that jazz often has. This music is obsessive, but cool, and tremendously stylish.

The soft keyboards and low-key string passages in “Of Helplessness” are more introverted, textural, moody and atmospheric, but do sometimes rise to more dramatic orchestral heights in a manner than reminds me of the more darkly romantic parts of Interview With the Vampire, or perhaps the finale of Howard Shore’s Silence of the Lambs. This sound continues on into “Coffee Shop,” which underscores the famous scene between De Niro and Pacino, and although the lead instrument switches from strings to piano, Goldenthal wisely keeps out of the way of these acting titans, letting their dialogue and simmering on-screen intensity do most of the work. This stands at odds with the resounding action of “Entrada and Shootout,” where Goldenthal makes use of more powerful orchestral sounds and heavy electronic percussion beats to underscore one of the film’s more vicious scenes of gun play. The conclusive “Of Separation” revisits the same general stylistics of “Of Helplessness,” and plays very much like a requiem, offering just over two minutes of darkly romantic, tonal pathos that ends the score on an emotional, but appropriately downbeat note.

The rest of the Heat album is given over to songs and instrumentals that Mann dropped into the film himself, and which basically function as ‘additional score’ but composed by Goldenthal. Two tracks of ambient electronic mood music, “Always Forever Now” and the pulsing “Force Marker,” are by English musician Brian Eno, with the former being written in collaboration with members of the Irish rock band U2. Two tracks, “Last Nite” and “Mystery Man,” are low-key chillouts by Norwegian jazz musician Terje Rypdal. Two tracks, the cinematic “La Bas” and the theatrical “Gloradin,” are by Lisa Gerrard, who would later go on to score Mann’s 1999 film The Insider (and of course work with Hans Zimmer on Gladiator); both have a deeply spiritual ‘world music’ sound that is quite captivating.

“Ultramarine” is by Michael Brook, who had also previously worked with both Brian Eno and The Edge from U2 on separate projects, and whose music shares a lot of stylistic similarities. “Armenia” is an indescribably avant-garde instrumental piece by German experimental music group Einstürzende Neubauten, one of whose members – Blixa Bargeld – co-founded The Bad Seeds with Nick Cave. Finally there are two tracks by dance music musician Moby: a remix of the 1979 Joy Division rock song “New Dawn Fades,” and a newer original song, “God Moving Over the Face of the Waters,” although the version that actually plays over the end titles is different from the one on the album. Goldenthal had actually written his own end titles piece, called “Hand in Hand,” but after it was rejected in favor the Moby song Goldenthal re-purposed it for the end titles of Michael Collins the following year.

All this is to say that Heat is a mixed bag of styles and approaches that offers a similarly mixed listening experience, depending on context. In the film, as I said, Mann’s insistence on chopping and changing and replacing large chunks of Goldenthal’s score with a mélange of electronica from a variety of sources left me mostly frustrated – anything that Goldenthal was trying to do, structurally and narratively, with his music, was destroyed by Mann’s micro-management, and so in the end you just have to accept that there is going to be no consistency or coherency, and take it for what it is. I will always prefer to have a single composer’s vision providing a film’s entire musical voice, but that’s never what you are going get with Michael Mann.

The album, however, is uniformly excellent. Goldenthal’s music comes alive when heard separately, a moody, introspective, creative exploration of what guitars, synths, and a string quartet can do when used with his idiosyncratic and highly personal composing style. The other songs and electronica tracks actually complement Goldenthal’s work very well too, resulting in surprisingly coherent and tonally compatible listening experience. Fans of Goldenthal’s more vivid orchestral works may find Heat something of a departure, and may have trouble connecting with it immediately, but patience reveals it to be satisfyingly different type of action thriller score.

Buy the Heat soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- Heat (7:40)

- Always Forever Now (written by Brian Eno, Paul Hewson, Adam Clayton, David Evans, and Larry Mullen Jr., performed by Passengers) (6:54)

- Condensers (2:33)

- Refinery Surveillance (1:43)

- Last Nite (written by Terje Rypdal, performed by Terje Rypdal & the Chasers) (3:29)

- Ultramarine (written and performed by Michael Brook) (4:34)

- Armenia (written by Blixa Bargeld, Mark Chung, Alexander Hacke, Jon Caffery, Frank Strauss, and Andrew Chudy, performed by Einstürzende Neubauten) (4:56)

- Of Helplessness (2:39)

- Steel Cello Lament (1:42)

- Mystery Man (written and performed by Terje Rypdal) (4:39)

- New Dawn Fades (written by Ian Curtis, Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris, performed by Moby) (2:54)

- Entrada and Shootout (1:45)

- Force Marker (written and performed by Brian Eno) (3:37)

- Coffee Shop (1:37)

- Fate Scrapes (1:34)

- La Bas (Edited Version) (written and performed by Lisa Gerrard) (3:10)

- Gloradin (written and performed by Lisa Gerrard) (3:56)

- Run Uphill (2:51)

- Predator Diorama (2:39)

- Of Separation (2:20)

- God Moving Over the Face of the Waters (written by Richard Hall, performed by Moby) (6:58)

Running Time: 73 minutes 30 seconds

Warner Bros. 9-46144-2 (1995)

Music composed by Elliot Goldenthal. Conducted by Jonathan Sheffer and Stephen Mercurio. Orchestrations by Elliot Goldenthal and Robert Elhai. Deaf Elk guitars performed by Page Hamilton, Eric Hubel, Bobby Hambel, and David Reid. Recorded and mixed by Joel Iwataki and Stephen McLaughlin. Edited by Christopher Brooks and Bill Abbott. Album produced by Elliot Goldenthal and Matthias Gohl.