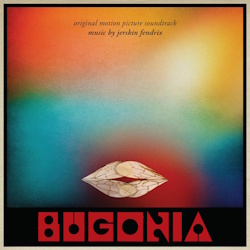

BUGONIA – Jerskin Fendrix

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

The term ‘bugonia’ comes from Latin and Greek, and relates to an ancient concept or myth describing the spontaneous generation of bees from the carcass of a dead ox. Philosophically and symbolically, bugonia reflects beliefs in the idea that living creatures can arise from non-living matter, as well as themes of death, rebirth, and transformation. In literary and religious contexts, it often serves as a metaphor for resurrection, drawing parallels between natural cycles and human or divine renewal. All this explains perfectly many of the underlying themes of director Yorgos Lanthimos’s new film, Bugonia. The film stars Jesse Plemons as disaffected conspiracy theorist Teddy Gatz, who has persuaded his autistic cousin Don (newcomer Aidan Delbis) to help him kidnap Michelle Fuller (Emma Stone), the wealthy and powerful CEO of a pharmaceutical megacorporation. Teddy has convinced himself that Michelle is secretly an alien from Andromeda who wants to destroy Earth, and he is determined to make her admit her true identity, and then take him to meet her ‘emperor’ so that he can initiate peace talks with them.

Bugonia is a remake of the 2003 South Korean film Save the Green Planet from director Joon-Hwan Jang, and I found it to be really quite excellent: it has some interesting things to say about corporate greed, the current political climate, environmentalism, conspiracy theories, and so much more. It’s also very funny at times, and features committed lead performances by Emma Stone, who willingly shaved her head for the role, and Jesse Plemons, who is by turns pathetic, frightening, and shockingly aware of the world’s problems. I predict it will be a major factor at the 2026 Oscars.

The score for Bugonia is by British composer and multi-instrumentalist Joscelin Dent-Pooley, better known by his professional nom-de-plume Jerskin Fendrix. Bugonia marks his third collaboration with Lanthimos after Poor Things in 2023 and Kinds of Kindness in 2024; he memorably received an Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe nomination for Poor Things, making him one of the few composers in history to receive such accolades for their first feature score.

Somewhat unusually, Fendrix was asked by Lanthimos to write the score based on nothing more than four key words: ‘bees,’ ‘basement,’ ‘spaceship,’ and ‘Emily bald.’ He was not provided with a script, additional context, or any actual footage, and simply had to conjure up in his mind what this could all mean in terms of the bigger scope of the film.

Somewhat unusually, Fendrix was asked by Lanthimos to write the score based on nothing more than four key words: ‘bees,’ ‘basement,’ ‘spaceship,’ and ‘Emily bald.’ He was not provided with a script, additional context, or any actual footage, and simply had to conjure up in his mind what this could all mean in terms of the bigger scope of the film.

In an interview with Jazz Tangcay for Variety Fendrix says he spent months researching those words and the concepts around them. “I looked into the different meanings and applications they could have, and then tried to see what kind of connective tissue I could find between them before actually writing the music.” He goes on to say he was “interested in geometric ideas, honeycombs, which are such a big part of the imagery around bees. That’s very representative of how uniform and equal, and also how complicated they are as a social structure. I saw a lot of things coming up through designs and systems in basements and other architectural theories to do with that. And, also, spaceships; there are literally spaceships that have honeycomb patterns on the side of them, because they tessellate in a way that seems conducive to their purpose.”

In terms of style, Fendrix says “the spaceship music was purely orchestral, the basement music was purely synthesizer, and then the bee stuff was a combination of the two.” Interestingly, Lanthimos didn’t use the music in the way Fendrix assumed he would, and in a second interview (with Jim Hemphill for Indiewire) Fendrix says that “I would’ve written a very different score if I’d known what the film was about. If I’d known that there was a great deal of the film that was dialogue-heavy and required space for the actors to have this really important discussion, I probably would have pulled back to a certain extent – and he obviously didn’t want that.”

All this has sparked some quite passionate back-and-forth about the nature of film scoring, specifically the way that Lanthimos asked Fendrix to work. As I discussed in my review of Mica Levi’s score for Jackie in 2016, many composers have been asked to write film music this way in the past, so this approach is not new. From Sergei Prokofiev on Alexander Nevsky, to more contemporary composers like Ennio Morricone and Hans Zimmer, there have been numerous instances where composers have written music for films prior to them being shot, based on impressions of the screenplay, or conversations with the director, or other things not related to the final cut of the movie. There is no one right way or wrong way to score a film, and many approaches are valid. What some people have railed against, though, is the overarching notion that this is not actual film scoring as we know it, in as much as Fendrix is not actually scoring a film as much as he is writing original library music which the director can then drop into the film anywhere he wants it. This has been a criticism of many of the most popular composers working today, notably Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross.

The crux of the issue is the fact that, as was the case with Levi’s Jackie, on Bugonia there was no way for Fendrix to consider the film’s pacing or editing, no way for him to consider the cinematography, no way for him to collaborate with the sound designers and sound editors to enhance or work with what they were doing. There was no way for him to bring out any particular nuances from the screenplay or the performances because he hadn’t seen them. There was no way he could enhance a particular moment in the film, or address any subtext, because he didn’t know when they occur, and didn’t know what the subtext was.

So, what does this all mean? Well, some would argue that the only thing that truly matters is how it all plays in film context, and from my point of view it actually works perfectly. Whether this is testament to Lanthimos’s skill as a storyteller, whether this is Fendrix’s intuition, whether it’s all a happy accident, or whether it’s some combination of all three, is up for debate, but whatever the reason the music in Bugonia works tremendously well.

In actuality, the fact that Fendrix didn’t know what sort of film he was writing for ultimately illustrates part of what Lanthimos is saying: the music sometimes feels too big and bombastic, as if it is underscoring something with much bigger stakes, life and death on a global scale, rather than the basement fantasies of a deluded conspiracy theorist. When the music explodes with huge, powerful brass flourishes, it’s saying ‘this is not just a scene of Teddy riding his bike around town; this is about the fate of the world’. The music’s overbearing scale and scope, and the juxtaposition of that against the working class mundanity of Teddy’s life, is eventually revealed to be the point. Like Fendrix, we don’t really know what’s going on at first. Not really. We’re just guessing.

The score was performed by the London Contemporary Orchestra and is, by turns, grandiose and classical, intimate and suspenseful, oddly charming, and even a little bit comedic, especially in the cues where Fendrix includes electronic tonalities, or writes with a slightly askew, off-kilter sensibility.

The ‘spaceship music’ that Fendrix describes is by far the most ear-grabbing part of the score. At the beginning of “Basement” it starts out dark and abstract, bulbous woodwind notes and nervous string textures offset against increasingly agitated percussion rumbles, but soon it explodes into the first of a series of massive, almost heraldic brass fanfares full of power and portent, Beethoven and Mozart at their most demonstrative.

The sound Fendrix generates here reminds me of some of the things Elliot Goldenthal was doing in his prime, especially when the trumpets start to squeal in pain; elsewhere I was reminded of the late Scott Walker’s 2015 score for director Brady Corbet’s Childhood of a Leader, which had similar emotional and tonal drivers (and which more people should discover). Similar eruptions of symphonic flamboyance can be heard in numerous subsequent cues, including the elegant and sweeping “Grand Cycle,” the fiercely strident and dramatic “Tell Teddy I’m Sorry” (which underscores one of the film’s most shocking scenes), the gigantic and brilliantly discordant “Grand Tango,” and the relentless “Ambulance Exit”.

Conversely, the music for the ‘bees’ concept feels very rooted in modern classical minimalism, and is full little repeated cells and buzzing string figures that aurally mimic the sounds of the titular insects, while also exploring the mathematical, geometric ideas Fendrix talked about in his Variety interview. In the opening cue, “Bees,” Fendrix surrounds these string patterns with some lovely, pastoral writing for woodwinds that comes across as his approximation of Ralph Vaughan-Williams’s evocation of the English countryside, The Lark Ascending and suchlike.

Extrapolations on this ‘bees’ idea can be heard elsewhere in the interplay between the woodwinds at the beginning of “Star Saliva,” in the keening strings of “Resurrectionem” and “Phantom Resurrectionem,” and in the peculiar trumpet militarism of “Eclipse Reveille”. An interesting offshoot of this is the demented circus-like sound in “Industry” and at the end of “Saliva Antifreeze,” both of which pit different parts of the woodwind section against each other, each competing to be the most dissonant, while the rest of the orchestra screams in protest.

Lanthimos actually ended up not using a great deal of the electronic ‘basement’ music that Fendrix penned for that concept, and so not much of it is present on the resulting album either. The best example of this sound is the “Spaceship” cue, which is experimental and unusual and appropriately alien-sounding, and sees Fendrix having a ball with a wide array of sound effects, whines, whistles, clicks and buzzers. It’s very different from everything else on the album but – again – it’s absolutely perfect for the scene it accompanies, and validates Lanthimos’s creative choice to use it when he does.

The brilliant “History of Earth” cleverly takes the classical ‘spaceship music’ and then twists and warps it through some accompanying synthesizer sounds, gradually slowing down the pitch and the speed further and further, eventually resulting in a sound which feels almost sickly, diseased, dying; again fantastic in context, especially when the film’s final development is revealed. The conclusive “CCD” has a similar sound, and sees Fendrix defacing a range of idyllic orchestral textures over the course of almost 10 minutes with a woodwind part that feels like a musical representation of decay. It’s a perfect tonal analogy to illustrate Lanthimos’s allegorical concept of ‘colony collapse disorder,’ a complex phenomenon in which worker bees abandon their hive. The way the cue just gently drifts away into nothingness is both poignant and meaningful.

The album also includes a version of Pete Seeger’s classic 1955 folk ballad “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” performed here by German screen legend Marlene Dietrich, and which in context plays over the film’s shocking final scene and into the end credits.

So, as I asked earlier, what does this all mean? Many will point to a score’s effectiveness in film context, and stop there, saying nothing else matters. The other argument, of course, is that the process of creation is just as important as the end result, and that by working the way he is, Yorgos Lanthimos is undermining the entire collaborative ethos of writing to picture, and denying Jerskin Fendrix the opportunity to actually craft music that is specifically tailored to the imagery on screen. Narrative musical storytelling is both a technical mathematical exercise and a deeply emotional art, and it’s a huge part of why I love film music the way I do.

However, from my point of view, I think that Bugonia is actually a perfect example of ‘the best of both worlds,’ and is a success in the same way that many of Ennio Morricone’s scores were a success when he wrote this way. Lanthimos gave Jerskin Fendrix the freedom to be completely creative and expressive with just the barest of narrative guidance, and then once Fendrix had written and recorded his music, Lanthimos was able to use it to make his film better and more impactful by structuring it in a way that even Fendrix didn’t expect. Results like this are rare; most often, this approach *doesn’t* work for me, but when it does, one has to give praise where praise is due.

One final thing I also want to really point out is just how engaging this score is from a purely musical point of view; the rhythmic choices, the orchestrations and arrangements, the performances, and the classical compositional techniques, are all top-notch. It really underscores the fact that Jerskin Fendrix has some seriously impressive musical chops, and proves that Poor Things was in no way a one-trick pony. Going forward I want to see Jerskin Fendrix being hired by other directors, and being asked to bring his talent out into the wider film music world. Get him to score a western, a period romance, an epic action adventure. I bet the results would be fantastic. Until then, look for Bugonia to give him his second Oscar nomination.

Buy the Bugonia soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- Bees (4:45)

- Basement (5:25)

- Star Saliva / Industry (5:19)

- Resurrectionem (2:14)

- Phantom Resurrectionem (5:16)

- Grand Cycle (1:22)

- Tell Teddy I’m Sorry (1:12)

- Grand Tango (1:48)

- Eclipse Reveille (3:32)

- Ambulance Exit (1:12)

- Spaceship (2:00)

- Where Have All the Flowers Gone (written by Pete Seeger and Joe Hickerson, performed by Marlene Dietrich) (3:39)

- Saliva Antifreeze (3:08)

- History of Earth (5:31)

- CCD (9:47)

Milan Records (2025)

Running Time: 56 minutes 10 seconds

Music composed and conducted by Joscelin Dent-Pooley (Jerskin Fendrix). Performed by the London Contemporary Orchestra. Orchestrations by Hugh Brunt and Ananda Chatterjee Recorded and mixed by Fiona Cruickshank. Edited by Graeme Stewart. Album produced by Jerskin Fendrix.

The grand instrumental score contains a musical phrase very reminiscent of Uprising by Muse. Given the ‘they will not control us’ in the lyrics, I thought it apropos but apparently not intentional