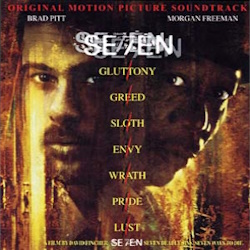

SEVEN – Howard Shore

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

The world is a fine place and worth fighting for. I agree with the second part. — Ernest Hemingway.

What’s in the box?!? — Detective David Mills.

Seven – usually stylized as ‘Se7en’ – is a dark psychological crime thriller written by Andrew Kevin Walker and directed by David Fincher, in what was his second feature film after his 1992 debut Alien 3. The film follows two homicide detectives – weary veteran William Somerset (Morgan Freeman), who is on the verge of retirement, and impulsive newcomer David Mills (Brad Pitt), who has recently transferred to the city with his wife Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow) – as they investigate a string of grisly murders staged around the seven deadly sins: gluttony, greed, sloth, lust, pride, envy, and wrath. Each crime scene is meticulously designed by the killer to reflect the sin being punished, and the murders grow increasingly disturbing. The investigation eventually leads the detectives to a deranged but calculating serial killer known only as John Doe (Kevin Spacey), who sees himself as a moral avenger exposing society’s corruption through his crimes, and whose final murder is directly targeted at the detectives investigating him.

Seven is a brilliant film, one of the best serial killer thrillers of the 1990s, and it was deeply influential in multiple ways. Its mixture of noir atmosphere, procedural detail, and psychological horror inspired later films and television series like Saw, The Bone Collector, True Detective, and even CSI, while the film’s rain-soaked, gritty, oppressive unnamed city setting became an archetype for depicting urban decay. The film’s famous climax is especially significant, and has been described as one of the most shocking and unforgettable plot twists in cinematic history; in it, a mysterious box is delivered to a desert location where Somerset and Mills are, inside of which is the severed head of Mills’s wife. Doe reveals that he murdered her because he was jealous of Mills’s seemingly normal life, making him the embodiment of envy; this leads to a devastated Mills executing Doe on the spot, completing the cycle as wrath. The film’s refusal to deliver catharsis – justice is never served, the villain “wins” by design, and the hero is morally compromised – challenged audiences and opened the door for significantly more nihilistic, morally gray narratives in mainstream cinema.

The music for Seven was by composer Howard Shore, who at the time was best known for his work on David Cronenberg films such as The Fly, Dead Ringers, and Naked Lunch, and for his score for the classic serial killer thriller The Silence of the Lambs. Seven was the first of three collaborations between Fincher and Shore (the others being The Game in 1997 and Panic Room in 2002), and it really set the tone for their partnership over the years.

The music for Seven was by composer Howard Shore, who at the time was best known for his work on David Cronenberg films such as The Fly, Dead Ringers, and Naked Lunch, and for his score for the classic serial killer thriller The Silence of the Lambs. Seven was the first of three collaborations between Fincher and Shore (the others being The Game in 1997 and Panic Room in 2002), and it really set the tone for their partnership over the years.

Shore was hired mainly on the strength of his work on Silence of the Lambs, and instead of writing a melodic or thematic score, he delivered a similarly ambient, brooding soundscape that’s unsettling, textural, and psychologically probing. Shore’s music avoids anything that could be described as ‘conventional beauty,’ instead writing music which is unremittingly bleak from start to finish. To achieve this he layers endlessly churning low strings against brass, percussion, piano, and electronic textures, creating an almost constant sense of dread, heightening the tension without release.

The opening cue on the album, “The Last Seven Days,” contains the score’s only real moment of optimism and lightness, but this cue was actually removed from the final cut of the film, and was instead replaced instead by a vicious remix of the already savage 1994 Nine Inch Nails song “Closer” by the experimental British electronica group Coil; NIN’s Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross would of course later collaborate directly with Fincher on The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Gone Girl, and Mank.

The rest of the score does not have any recurring themes per se, but Shore does use a couple of very small motifs throughout. The first is a descending seven-note idea that represents John Doe himself – seven notes, seven deadly sins – and which underpins many of the scenes where Somerset and Mills explore crime scenes and gradually piece together the gruesome puzzle that he has left for them. Once or twice Shore reverses the flow of the John Doe theme, ascending rather than descending, and uses it as a brief idea for Gwyneth Paltrow’s character Tracy, indicating that her goodness and kindness is the opposite of Doe’s evil, while also subtly foreshadowing her horrific fate. The performance of her theme in “Mrs. Mills” is full of iridescent and warm woodwind textures, creating a surreally enticing ambiance.

Throughout cues such as “Gluttony,” “Linoleum,” the disconcerting “Greed,” “Help Me,” the eerie and tortuous “Lust,” and the hauntingly guttural “Pride,” there is a palpable sense of foreboding and inevitability to Shore’s writing. The music creeps and groans, twists and contorts, and insidiously gets under your skin. Long cello chords are echoed by similarly drawn-out brass counterparts, while skittery violin textures play off them, and eerie metallic scrapes dance around the fringes of the orchestra. There is a sense of sickness, disease, and decay to this music, which makes it incredibly difficult to listen to, but it adds to the fetid atmosphere of the movie enormously. As I mentioned earlier, in terms of Shore’s career this music can be seen very much as a variation on the music heard during the finale of The Silence of the Lambs, when Clarice Starling is stumbling blindly around the basement of Buffalo Bill’s house, while he stalks her in the dark, albeit here extended to an entire score.

The second recurring idea is a more rhythmic, pulsating motif, an offshoot of the final three notes of the John Doe theme, which Shore uses during the film’s various chase sequences – notably “Sloth” – and then especially in the desert-set finale. The music in these sequences is bolder, more symphonically rich, and sometimes quite grand, using larger brass forces and layering them against crashing pianos, taiko drums, and other dramatic percussion sounds, along with shrill metallic textures. Fascinatingly, some of the brass phrases in these cues sometimes feel like dry runs for what would eventually become the ‘ringwraith’ music from his Lord of the Rings scores, proving yet again that everything he did in those masterpieces has its roots in his earlier filmography.

Shore calls “John Doe” and “Apartment #604” the emotional musical center of the film, as they underscore the scene where Somerset and Mills finally discover Doe’s lair. Shore uses an intricate range of metallic percussion devices – celeste, xylophone, bowed tams – to create a subliminal scream of anguish underneath the orchestra. Shore then blends this sound with references to both the main John Doe theme and the pulsating action motif, creating an aural nightmare that is somehow thrilling and exhilarating, but also deeply creepy. The brass writing in “John Doe” is especially brutal, a relentless onslaught.

In the conclusive sequence comprising “The Wire,” “Envy,” and “Wrath,” Shore ratchets up the tension to unbearable levels; first as Somerset and Mills interrogate Doe about his motivations during the car ride to the final location out in the desert, and then as an unwitting FedEx driver delivers perhaps the most notorious package box in cinema history, leading to the final confrontation between the trio and the culmination of Doe’s plans. Again, Shore blends the 7-note John Doe theme with the pounding taikos and timpanis, and he gradually increases the pressure through endlessly repeated string and brass patterns, until it all eventually erupts into a violent rage of fury and anguish.

The original 1995 soundtrack album from TVT records was a somewhat peculiar release, as it comprised mostly of vintage jazz tracks by people like Charlie Parker and Theolonious Monk, plus a few light rock songs and classical pieces. Tacked onto the end are two score tracks, “Portrait of John Doe” and “Suite from Seven,” which comprised 20 minutes of music arranged as elongated suites. The music is a decent enough representation of what Shore wrote, but the way it is presented leaves much to be desired, as scene specificity is completely ignored. Unusually, neither the Coil remix of Nine Inch Nails’ “Closer,” nor the David Bowie’s song “The Hearts Filthy Lesson” which plays over the end credits, appear on this album, a bizarre oversight considering their prominence in the film itself. Thankfully, albeit 20 years late, in 2016 Shore and producer Alan Frey released a proper hour-long score album on Shore’s own label Howe Records, and this is the album being reviewed here.

The original 1995 soundtrack album from TVT records was a somewhat peculiar release, as it comprised mostly of vintage jazz tracks by people like Charlie Parker and Theolonious Monk, plus a few light rock songs and classical pieces. Tacked onto the end are two score tracks, “Portrait of John Doe” and “Suite from Seven,” which comprised 20 minutes of music arranged as elongated suites. The music is a decent enough representation of what Shore wrote, but the way it is presented leaves much to be desired, as scene specificity is completely ignored. Unusually, neither the Coil remix of Nine Inch Nails’ “Closer,” nor the David Bowie’s song “The Hearts Filthy Lesson” which plays over the end credits, appear on this album, a bizarre oversight considering their prominence in the film itself. Thankfully, albeit 20 years late, in 2016 Shore and producer Alan Frey released a proper hour-long score album on Shore’s own label Howe Records, and this is the album being reviewed here.

I say thankfully, because your reaction to the music from Seven may actually be a negative one, depending on your tolerance for music that is expressly designed to unsettle you and make you feel uncomfortable. Make no mistake, Seven is a tough score. It is music that is intended to be almost entirely devoid of hope and warmth, and instead it seeks to convey the most corrupt and immoral parts of the human psyche, the depraved lengths someone will go to in order to prove a warped point. From that point of view, what Shore did here is a complete success, and anyone who can intellectualize that may glean something from it. Others; beware. While the film itself offers seven deadly sins, Howard Shore potentially offers an eighth: the sin of dissonance, the refusal of resolution, and the deliberate cultivation of sounds that disturb without offering release, or perhaps the sin of cacophony, the willful crafting of disharmony and sonic violence to trap the soul in unease. John Doe himself would likely approve.

Buy the Seven soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- SOUNDTRACK ALBUM

- In the Beginning (written by Ben Weisman, Dorcas Cochran, Fred Wise, and Kay Twomley, performed by The Statler Brothers) (2:22)

- Guilty (written by Jeff Scheel, Matt Dudenhoffer, Douglas Firley, and Kurt Kerns, performed by Gravity Kills) (4:05)

- Trouble Man (written and performed by Marvin Gaye) (3:50)

- Speaking of Happiness (written by Buddy Scott and Jimmy Ratcliffe, performed by Gloria Lynne) (2:33)

- Suite No. 3 in D, BWV 1068: Air (written by Johann Sebastian Bach, performed by Stuttgarter Kammerorchester, cond. Karl Munchinger) (3:39)

- Love Plus One (written by Nick Heyward, performed by Haircut 100) (3:38)

- I Cover the Waterfront (written by Edward Heyman, performed by Billie Holiday) (3:20)

- Now’s The Time (written and performed by Charlie Parker) (4:16)

- Straight, No Chaser (written and performed by Thelonious Monk) (9:38)

- Portrait of John Doe (4:57)

- Suite from Seven (14:50)

- SCORE ALBUM

- The Last Seven Days (2:14)

- Gluttony (5:44)

- Linoleum (2:24)

- Somerset (1:04)

- Greed (3:39)

- Mrs. Mills (1:05)

- Help Me (3:31)

- Sloth (5:29)

- Library (2:19)

- John Doe (6:02)

- Apartment #604 (4:15)

- Lust (3:52)

- Pride (4:01)

- The Wire (3:15)

- Envy (7:09)

- Wrath (5:16)

Running Time: 57 minutes 08 seconds – Soundtrack

Running Time: 61 minutes 09 seconds – Score

TVT Records/Cinerama 0022432CIN (1995) – Soundtrack

Howe Records HWR-1012 (1995/2016) – Score

Music composed by Howard Shore. Conducted by Lucas Richman. Orchestrations by Bert Dovo and John Lissauer. Recorded and mixed by John Kurlander and John Richards. Edited by Ellen Segal and Angie Rubin. TVT album produced by Patricia Joseph. Howe album produced by Howard Shore and Alan Frey.