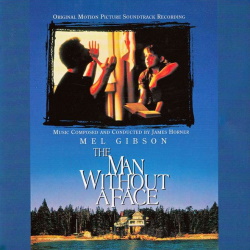

THE MAN WITHOUT A FACE – James Horner

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

The Man Without a Face is a drama film about the unlikely friendship between a teacher and a student, and is based on the 1972 novel of the same name by Isabelle Holland. It was the directorial debut of Mel Gibson, who also stars in the eponymous role as Justin McLeod, a former teacher who was disfigured in a car accident, leaving him with severe facial burns, and who now lives a reclusive life on an island off the coast of Maine, estranged from society due to his appearance and his emotional scars. Things change for McLeod when a teenage boy named Chuck Norstadt, who is struggling with his studies and is on the verge of flunking out of the military school he desperately wants to attend, approaches him for help with his education. Despite initial hesitation from Chuck’s mother, they form an unlikely friendship, and McLeod agrees to tutor the boy in various subjects. As the summer progresses, McLeod’s mentorship helps Chuck not only academically but also emotionally, while Chuck’s faith in McLeod starts to help him shed some of his bitterness and anger. However, rumors and misunderstandings about the ‘true nature’ of their relationship begin to circulate in the small town, leading to suspicion and hostility. The film co-stars Nick Stahl as Chuck, as well as Margaret Whitton, Fay Masterson, Gaby Hoffmann, Geoffrey Lewis, and Richard Masur. It received mostly positive reviews from critics at the time, although it is somewhat forgotten today.

I have always been fond of ‘inspirational teacher’ movies, with Dead Poets Society being one of my favorites, but I have always appreciated The Man Without a Face too. It’s an earnest, heartfelt, but also slightly sad and bittersweet movie, which looks at the way society often treats outsiders – especially ones with facial disfigurements – with fear and contempt. The film excises many of the book’s blatant undercurrents of homosexuality and paedophilia, but there are still subtle allusions to the topics here, which makes for an important subtext. It also was one of the first films where I saw Mel Gibson in a new light, having previously only really known him as a wisecracking action hero from the Lethal Weapon movies. Here he shows that he is clearly an accomplished actor and director with a more sensitive and mature side. His next movie after The Man Without a Face was Braveheart, and we all know how much I love that film, historical inaccuracies be damned.

The score for The Man Without a Face was by James Horner, and was the seventh of the ten films he scored in 1993, following on the heels of titles like Swing Kids, A Far Off Place, Jack the Bear, Once Upon a Forest, House of Cards, and Searching for Bobby Fischer. Horner had not scored a Mel Gibson film prior to this one, but something about their working relationship clicked, and Gibson inspired Horner to write outstanding music across several films; not only this film and Braveheart, but also Apocalypto in 2006. Horner had also signed on to score Hacksaw Ridge in 2016, but died before he started work on it.

The score for The Man Without a Face was by James Horner, and was the seventh of the ten films he scored in 1993, following on the heels of titles like Swing Kids, A Far Off Place, Jack the Bear, Once Upon a Forest, House of Cards, and Searching for Bobby Fischer. Horner had not scored a Mel Gibson film prior to this one, but something about their working relationship clicked, and Gibson inspired Horner to write outstanding music across several films; not only this film and Braveheart, but also Apocalypto in 2006. Horner had also signed on to score Hacksaw Ridge in 2016, but died before he started work on it.

Much like the film it accompanies, the score is serious and earnest, but also hopeful and optimistic, and often erupts into moments of great harmonic consonance when the narrative requires it. It was recorded in London with the London Symphony Orchestra, which means that the performance is impeccable, and the recording quality is noticeably crisp and clear, so that the depth of the orchestration stands out. Horner writes notable solos for piano, cello, mixed woodwinds, and French horn, always backed by the lushness of the string orchestra, and there are several recurring themes, although the direct application of them appears to be more concept-based than character-based; what I mean is that, for example, there is no specific theme for McLeod, no specific theme for Chuck, and so on, but instead the themes tend to relate to their friendship, McLeod’s memories of his past, the concept of teaching, etc. What this tends to mean is that the score is a bit ephemeral; it’s hard to delineate where one thematic idea ends and another begins. But one thing’s for sure: the score is very beautiful.

The opening cue, “A Father’s Legacy,” is a lovely introduction to the score, presenting several different thematic ideas in sequence, all of them warm, appealing, but perhaps underpinned with a touch of darkness. The theme that begins at 1:27 is one of the score’s emotional touchstones, and it receives several prominent performances later in the score, notably in the more dramatic “Lost Books,” and then in the quietly devastating “The Tutor,” which carries the weight of McLeod’s past in its long-lined thematic statements.

There is some beautiful, bittersweet writing for piano and harp in “Chuck’s First Lesson,” which leads into a hesitant statement of the main theme on oboes. Later cues like “McLeod’s Secret Life” and “The Merchant of Venice” are a little more subdued, offering a delicate balance between melancholy and uplifting, underscoring the drama with tonally appealing music, but never really drawing much attention to themselves. There is a tone of something approaching playfulness in “McLeod’s Last Letter,” though, which has a wholesome quality emanating from its pretty writing for strings, horns, and flutes.

One of the score’s highlights for me is “Flying,” a warm and cheerful variation on the four-note motif that ran through much of the score for Sneakers and which is, basically, a less evil version of the ‘danger motif’ heard throughout Horner’s entire career. The second half of the cue is just delightful, a heartwarming celebration of the freedom of aviation, which sees the orchestra underpinned with light percussive rhythms and a lively guitar, following the flow of the seaplane as it skims along the surface of a gorgeous lake.

On the other hand, “Nightmares and Revelations” uses the four-note motif in its much more familiar sinister role, rumbling deep down in the mix amid a bed of low bass dissonance that underscores the scene where McLeod reveals to Chuck how he came by his facial injuries in the first place. Some of the searing high string work in this cue foreshadows the ‘Robert the Bruce’s betrayal’ music from Braveheart, and has a similar emotional impact.

Some of the chord progressions, instrumental combinations, and general tonalities, are quintessential Horner; there are echoes of earlier scores like The Land Before Time, as well as foreshadowings of the more serious and deeply-felt parts of scores like Braveheart and even Casper, the latter of which also deals with the fallout from the death of a child. I find several little touches that Horner uses throughout the score very appealing; he often phrases his pianos in a call-and-response manner, an upward-inflected two-note motif followed by a downward-inflected cascade that is just gorgeous. He also often precedes thematic statements with a noticeable ‘shimmer,’ either from the violins or the piano, which sort of hints at the hesitancy in the relationship between McLeod and Chuck, with neither one fully sure whether to trust the other.

The final two cues, “No Compromise” and “Lookout Point/End Credits,” run for a combined total of more than 12 minutes, and contain some bold dramatic crescendos, moments of great pathos, and several ravishing statements of the main thematic ideas, all gradually building up to the final scene where Chuck – having used McLeod’s tutelage to realize his dream of graduating from the military academy – sees the banished and vilified McLeod cautiously watching him from the perimeter of the parade ground, and they exchange a wordless look of gratitude, recognition, and mutual respect. Horner’s music acknowledges their friendship with warmth and grace via a gorgeous statement of the main theme beginning at the 2:19 mark, but the piece is underpinned with the poignant knowledge that neither of them will see each other again. These cues are bisected by a performance of the dramatic aria “Ch’ella Mi Creda” from Puccini’s opera La Fanciulla del West, performed by Swedish tenor Jussi Björling, which is just superb.

The Man Without a Face is a lovely score; it’s lush, appealing, and filled with gorgeous melodic ideas, but having said that I can see how it may come across as something of a slow burn for anyone who demands a little more energy from their film music. In addition, the somewhat tenuous nature of some of the thematic application may result in some finding it a little meandery at times, perhaps lacking in an obvious melodic core on which to latch. Personally, though, I love it, and for me it remains one of the most appealing straight drama scores from that period in James Horner’s career.

Buy the Man Without a Face soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- A Father’s Legacy (6:14)

- Chuck’s First Lesson (2:49)

- Flying (3:49)

- McLeod’s Secret Life (1:58)

- Nightmares and Revelations (4:22)

- McLeod’s Last Letter (2:58)

- Lost Books (1:57)

- The Merchant of Venice (2:55)

- The Tutor (3:21)

- No Compromise (4:56)

- Ch’ella Mi Creda from La Fanciulla del West (written by Giacomo Puccini, performed by Jussi Björling) (2:26)

- Lookout Point/End Credits (7:57)

Running Time: 45 minutes 42 seconds

Philips 314 518 244-2 (1993)

Music composed and conducted by James Horner. Orchestrations by Thomas Pasatieri. Recorded and mixed by Shawn Murphy. Edited by Jim Henrikson. Album produced by James Horner.

I was listening to this score again only a few days ago. Horner was so good at scoring films like this. He just had this gift for emotion and drama: I have so many of his scores on CD, I’m always drawn to the quieter, more intimate stuff than the big loud action filmscores, I mean, he was fine at that, but its the emotional material where he truly exceled, and what I really miss in films these days.

Agreed 100%.