Double Lives or Double Standards? Concert works by film composers

Anyone who has encountered a film composer in their natural habitat knows that this unassuming species is at their best in the midst of a busy recording studio, scribbling last-minute changes to orchestrations and wrangling reluctant musicians to play new pieces in weird time signatures, all the while politely fielding queries from cloth-eared directors who ask things like, “This bit should sound more like the bit from Jaws – you know the bit, right?” or “Can you give me more oomph here? We need more oomph.” If you think I’m joking, recall that Bernard Herrmann once said of Hitchcock that the great auteur would happily have had all his movies underscored with Ketèlbey’s In a Monastery Garden if he could.

When confronted with a blank sheet of paper instead of a screen or a screenplay, our affable film composer might understandably feel a little bereft, like a director without a camera or an actor without a script. But there’s an even bigger problem. Any resulting concert-hall work risks falling between two off-puttingly large stools: first, the expectations of film music fans who have gotten used to bite-sized soundtrack cues and are generally not interested in longer-form works lacking any visual associations; and second, the sniffy attitude of the classical music community towards such journeymen (and women) getting ideas above their station – recall the notorious New York Times review of Korngold’s Violin Concerto in 1947: “more Korn than Gold”. Attitudes have changed since then, but not entirely.

Korngold, of course, came to film music after great success in the concert-hall (The Adventures of Robin Hood score even includes chunks of his Sursum Corda overture). To a lesser extent this was also the case with Miklós Rózsa, who pointedly lived what he himself referred to as his “Double Life” – continuing to write concert-hall works alongside his film commissions. Bernard Herrmann and Franz Waxman also attempted to write non-film music with, it must be said, not a great deal of success: Herrmann’s only opera, Wuthering Heights, was never staged in his lifetime (it was finally performed in full in 2011).

It’s all the more gratifying, therefore, to note what seems to be an increasing willingness on the part of contemporary film composers to essay works for the concert hall. Cynics might suggest (and they might not be wrong) that it’s a marketing ploy by record companies faced with declining sales of traditional classical repertoire. We might respond with equal cynicism that if ‘serious’ contemporary composers had bothered to write music that audiences actually liked then there would have been no such decline in the first place. But we are where we are, and the questions remain: can these new concert-hall works find an audience? Will film music fans accept them? Will connoisseurs of concert music deign to notice them? And are any of them good enough anyway?

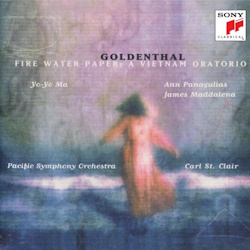

The modern trend for promoting film composers on classical labels arguably began with Sony Classical back in the 1990s, specifically with Elliot Goldenthal’s Fire Water Paper: A Vietnam Oratorio. Goldenthal was a rising star in Hollywood at the time, whose filmography included Interview with the Vampire, Heat and Batman Forever. But as a former pupil of John Corigliano he also had the credentials to satisfy (in theory at least) the critical classical music world. Fire Water Paper was given a glitzy premiere performance in Los Angeles in 1995 and was subsequently recorded with Yo-Yo Ma as the cello soloist. It seemed at the time like a sure bet. The recording was warmly received by Gramophone magazine, whose reviewer praised the composer’s “imaginative flair and extraordinary assurance”. It is to be sure a striking and eclectic piece, possibly too eclectic: as befitting a composer with such a sense for the dramatic, this is a work that thrilled in the concert hall (I know, I was there!) but makes for a somewhat disjointed listening experience. As Gramophone’s reviewer also tactfully noted, it owes a few too many stylistic debts to the likes of Mahler and Shostakovich to be satisfactory on its own.

The modern trend for promoting film composers on classical labels arguably began with Sony Classical back in the 1990s, specifically with Elliot Goldenthal’s Fire Water Paper: A Vietnam Oratorio. Goldenthal was a rising star in Hollywood at the time, whose filmography included Interview with the Vampire, Heat and Batman Forever. But as a former pupil of John Corigliano he also had the credentials to satisfy (in theory at least) the critical classical music world. Fire Water Paper was given a glitzy premiere performance in Los Angeles in 1995 and was subsequently recorded with Yo-Yo Ma as the cello soloist. It seemed at the time like a sure bet. The recording was warmly received by Gramophone magazine, whose reviewer praised the composer’s “imaginative flair and extraordinary assurance”. It is to be sure a striking and eclectic piece, possibly too eclectic: as befitting a composer with such a sense for the dramatic, this is a work that thrilled in the concert hall (I know, I was there!) but makes for a somewhat disjointed listening experience. As Gramophone’s reviewer also tactfully noted, it owes a few too many stylistic debts to the likes of Mahler and Shostakovich to be satisfactory on its own.

While Goldenthal’s Hollywood star has waned somewhat in recent years, he has continued with his non-film composing, completing, among others, a ballet score Othello and an opera, Grendel (2006) – which, judging from the online reviews, was not a success. He set up his own label, Zarathustra music, and has to date released a few albums of his concert works, including a Symphony in G# minor (2014) that features a moody and atmospheric first movement and a second movement chock full of Goldenthal-esque rhetorical gestures.

Even more recently (2024), Cliff Eidelman released a streaming-only album featuring his Symphony No. 2. With prominent roles for mezzo-soprano and piano, it’s a lively, entertaining piece and has much of the same charm as Eidelman’s film work – the final movement, for me, being the standout. But I’m not entirely convinced that the description ‘symphony’ does either Goldenthal or Eidelman any favours; while I appreciate they may want to distance these pieces from any programmatic associations, the term symphony comes with a lot of heavyweight historical baggage. A tone poem, an orchestral fantasy, an overture – or just a simple orchestral piece with an intriguing name – might better describe them. You can hear them for yourself on streaming platforms and judge for yourself.

Bruce Broughton, another composer who seems to have been almost criminally neglected in Hollywood, has a long history of writing for the concert hall. Naxos have (June 2024) released an album of two extensive new pieces performed by the London Symphony Orchestra: And on the Sixth Day (an oboe concerto) and String Theory. The album originally included a Horn Concerto as well, but for mysterious reasons this seems to have been removed. What we are left with are two works that showcase Broughton’s skilful use of his orchestral palette – which could broadly be described as ‘Americana’ somewhere in the tradition of Copland and, dare I say it, John Williams – without either of them making a particularly strong impression.

Bruce Broughton, another composer who seems to have been almost criminally neglected in Hollywood, has a long history of writing for the concert hall. Naxos have (June 2024) released an album of two extensive new pieces performed by the London Symphony Orchestra: And on the Sixth Day (an oboe concerto) and String Theory. The album originally included a Horn Concerto as well, but for mysterious reasons this seems to have been removed. What we are left with are two works that showcase Broughton’s skilful use of his orchestral palette – which could broadly be described as ‘Americana’ somewhere in the tradition of Copland and, dare I say it, John Williams – without either of them making a particularly strong impression.

Howard Shore’s eclectic film CV – from the creepy body horror of early Cronenberg to the romantic grandeur of Middle Earth – gives us little hint of what his concert-hall music might sound like. It’s unsurprising then that his album of selected works, A Palace Upon the Ruins (Howe Records, 2016) is also pretty eclectic: a song-cycle with German lyrics in high romantic style, works for choir that nod in the direction of Lothlorien, and other colourful, atmospheric pieces that intrigue in a meandering sort of way. Somewhat more ambitious are his Piano Concerto “Ruin and Memory” premiered and recorded by Lang Lang, coupled with a Cello Concerto “Mythic Gardens” (Sony Classical, 2017, re-released on Howe Records). Rather like Broughton’s, Shore’s concert music is always impressively constructed but has something of a hesitant quality, as if the composer is unwilling to impose too much of a strong identity on the music. The result is too often a close affinity with established classical repertoire at the expense of an original musical voice. Film composers spend so much of their lives mimicking the styles of others that they sometimes forget to develop their own.

We might reasonably expect a more forthright statement of personality from Danny Elfman, whose instantly identifiable musical style on films like Edward Scissorhands, A Nightmare Before Christmas and Batman won him legions of fans. Both his Violin Concerto “Eleven Eleven” (2019) and Percussion Concerto (2024 – both albums released on Sony Classical) are indeed substantial and highly entertaining works that manage the neat trick of combining twentieth-century classical influences (Prokofiev, Shostakovich) with those signature Elfman-esque flourishes. Honestly, I’d be even happier if they had fewer nods to their predecessors and more of the wacky Elfman-isms. But if anyone can make the transition from screen to concert hall, surely it is Elfman.

Another strong, original voice was Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, a meteorically rising star in film music circles before his untimely demise in 2018. Jóhannsson scored the movies that brought director Denis Villeneuve to everyone’s attention – Prisoners, Sicario and Arrival – and won a Golden Globe for The Theory of Everything in 2015. At the same time he was developing an impressive CV as a composer of often abstract, ambient concert works. His album Orphée (DG, 2017) includes the minimalist piano piece “Flight from the City”, which has deservedly taken on something of a life of its own. More recently, his Drone Mass (DG, 2022) was glowingly received by reviewers. While hardly qualifying as easy listening, this striking and forthright work demands the listener’s attention: at times it has a Koyaanisqatsi-like sense of rhythmic urgency, at others the voices eerily set against electronics seem imbued with a strange atavistic quality.

What many of the works discussed so far tend to lack is … a big tune. Since the mid-twentieth century memorable, hummable melodies have been infra dig. in the serious music world. Fortunately for audiences, Japanese composer Joe Hisaishi seems not to have gotten the memo. His film scores – mostly for the wondrous animations of Studio Ghibli – are gorgeous, old-world romantic, and gleefully tuneful. Deutsche Grammophon’s A Symphonic Celebration (2023) album is a case in point: delightful suites from some of Hisaishi’s many collaborations with Hayao Miyazaki. Hisaishi has now joined the ranks of the crossover composers with his latest release, also on DG, Joe Hisaishi in Vienna (2024), an album that includes two new orchestral works: his Second Symphony and a Viola Concerto. As a concert composer, Hisaishi is a fascinating blend of Mahler fanboy, modern minimalist, and Japanese musical folklorist. It’s a refreshing combination. The symphony certainly has minimalist underpinnings but still features bold, folk-like themes, and the whole is irresistibly coloured by Hisaishi’s vibrant cinematic palette. The two-movement Viola Saga is more Michael Nyman-like in its insistent minimalism (or should that be Bach? Nods to the Cello Suites here). With his recent appointment as Composer-in-Association to the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra there’s likely to be a lot more of this sort of thing from Hisaishi, who is finally in a position to champion his own charming film-concert crossover music.

What many of the works discussed so far tend to lack is … a big tune. Since the mid-twentieth century memorable, hummable melodies have been infra dig. in the serious music world. Fortunately for audiences, Japanese composer Joe Hisaishi seems not to have gotten the memo. His film scores – mostly for the wondrous animations of Studio Ghibli – are gorgeous, old-world romantic, and gleefully tuneful. Deutsche Grammophon’s A Symphonic Celebration (2023) album is a case in point: delightful suites from some of Hisaishi’s many collaborations with Hayao Miyazaki. Hisaishi has now joined the ranks of the crossover composers with his latest release, also on DG, Joe Hisaishi in Vienna (2024), an album that includes two new orchestral works: his Second Symphony and a Viola Concerto. As a concert composer, Hisaishi is a fascinating blend of Mahler fanboy, modern minimalist, and Japanese musical folklorist. It’s a refreshing combination. The symphony certainly has minimalist underpinnings but still features bold, folk-like themes, and the whole is irresistibly coloured by Hisaishi’s vibrant cinematic palette. The two-movement Viola Saga is more Michael Nyman-like in its insistent minimalism (or should that be Bach? Nods to the Cello Suites here). With his recent appointment as Composer-in-Association to the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra there’s likely to be a lot more of this sort of thing from Hisaishi, who is finally in a position to champion his own charming film-concert crossover music.

It would be remiss to conclude without mentioning the daddy of them all, John Williams, whose discography of non-film recordings extends back to the 1970s, when the original version of his first Violin Concerto (1974) coupled with an atonal Flute Concerto (1969) appeared on the Varèse Sarabande label. Since then Williams has persevered in his own double life with a series of recent recordings including his Second Violin Concerto premiered by Anne-Sophie Mutter (DG, 2022). Among his legions of film music fans, the reception of these works has often been oddly muted. His filmic fame rests on those Golden Age, Korngold-inspired scores (Star Wars, Harry Potter etc). By contrast his concert music is discursive, at times meandering, often elusive, lacking an obvious tonal centre, definitely lacking any hummable tunes. As exemplified by this new Violin Concerto, his concert works are always beautifully, flawlessly scored and display his absolute mastery of the orchestra. But do they move the emotions, do they excite the listener? I confess I for one still struggle with that. For me, the most attractive of them is the beguiling bassoon concerto Five Sacred Trees (Sony Classical, 1997), a mysterious yet playful piece that occasionally threatens to break out into melody and recalls in its orchestration some of his best film work (for example, the fourth movement Craeb Uisnig owes a debt to Dagobah from The Empire Strikes Back).

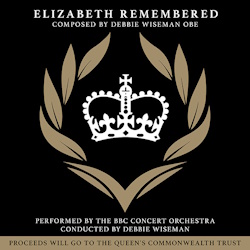

Will any of the pieces discussed here enter mainstream repertoire? Considering that it took at least 50 years for Korngold’s great concerto to win any sort of acceptance, we probably have a few years to wait before we know for sure. John Williams – if only by virtue of his fame – may yet win over concert-goers. So too might Danny Elfman. And it would be a rash gambler who bet against the unflappable, indefatigable Joe Hisaishi. For my part, I would not want to overlook the work of Debbie Wiseman, composer-in-residence at Classic FM since 2015, who has quietly, steadily been building an impressive body of non-film works, albeit fairly small-scale, including her lovely tribute to the late Queen, Elizabeth Remembered. It’s only a matter of time before Wiseman gives us a more substantial concerto or symphony, and when she does it’s bound to be ravishingly gorgeous. In the meantime, I’ve got my fingers crossed that Hans Zimmer comes up with a proper banger …

Will any of the pieces discussed here enter mainstream repertoire? Considering that it took at least 50 years for Korngold’s great concerto to win any sort of acceptance, we probably have a few years to wait before we know for sure. John Williams – if only by virtue of his fame – may yet win over concert-goers. So too might Danny Elfman. And it would be a rash gambler who bet against the unflappable, indefatigable Joe Hisaishi. For my part, I would not want to overlook the work of Debbie Wiseman, composer-in-residence at Classic FM since 2015, who has quietly, steadily been building an impressive body of non-film works, albeit fairly small-scale, including her lovely tribute to the late Queen, Elizabeth Remembered. It’s only a matter of time before Wiseman gives us a more substantial concerto or symphony, and when she does it’s bound to be ravishingly gorgeous. In the meantime, I’ve got my fingers crossed that Hans Zimmer comes up with a proper banger …

Discography:

- Bruce Broughton – And on the Sixth Day, String Theory (Naxos)

- Cliff Eidelman – Symphony 2 (streaming only)

- Danny Elfman – Violin Concerto “Eleven Eleven”, Piano Quartet (Sony Classical), Percussion Concerto, Wunderkammer (Sony Classical,)

- Elliot Goldenthal – Fire Water Paper (Sony Classical), Symphony in G# Minor (Zarathustra), Othello ballet (Varèse Sarabande)

- Joe Hisaishi – Symphony 2, Viola Saga (DG)

- Jóhann Jóhannsson – Orphée (DG), Drone Mass (DG)

- Howard Shore – A Palace Upon the Ruins (Howe Records), Ruin and Memory, Mythic Gardens (Howe Records)

- John Williams – Violin Concerto 2 (DG), Five Sacred Trees (Sony Classical)

- Debbie Wiseman – The Music of Kings and Queens (Decca)

Once upon a time, a long, long, time ago, Mark Walker had the idea to create a guide to soundtracks on CD, organised by composer not film title, something no one at the time had done. The result was the Gramophone Film Music Good CD Guide (1996). His passion for movie music remains (almost) undimmed to this day.

Don’t forget the incredible concert works on the album “Hubris” by the great John Powell!

I did forget that! Thanks for the reminder. Not sure how I feel about that album – the very fact that I forgot about it isn’t a great indication. But I will definitely go back and give it another try.

The downside is that the approachability of film music feeding back into the concert hall has resulted in something that Andy Vores has tellingly dubbed ‘the New Niceness’ (qv Rebecca Dale). I’m all for music that people will like, but gene-splicing Eric Coates with Mantovani is a slippery slope…

I enjoy John Williams’ concert works, despite (or perhaps because of) their complete detachment from his film music. There are parts of his cello concerto and second violin concerto that are among the most beautiful music he’s written in years.

One of the many reasons I’m still gutted by James Horner’s death is that he was expanding into classical music in his last years, as exemplified by his Pas de Deux and Collage pieces.

I don’t know if you’ve checked this out yet, but Benjamin Wallfisch also has quite a few classical pieces in his repertoire, having started from that world before entering film scoring!