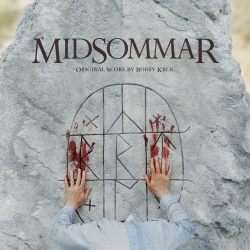

MIDSOMMAR – Bobby Krlic

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

Original Review by Jonathan Broxton

Although horror movies are pervasive and very popular in cinematic culture, one particular sub-genre of horror is not explored with as much frequency as others, and that is ‘folk horror,’ where the crux of the plot is derived from characters’ adherences to ancient pagan rituals in an otherwise contemporary setting. The most popular and well-known of these prior to this year was probably the 1973 British film The Wicker Man (we’re forgetting the risible Nicolas Cage remake), but director Ari Aster’s Midsommar looks set to challenge its status as the pre-eminent example of its genre. Whereas Aster’s debut film Hereditary explored the dark corners of devil worship in contemporary America, Midsommar takes place in the bright sunshine of Sweden. Florence Pugh plays Dani, a college student struggling to cope with the murder-suicide of her sister and parents, and whose boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor) is distant and disinterested. Christian and two of his friends, Mark and Josh, are invited by another friend, Pelle, to spend the summer at Pelle’s home in Sweden; Pelle grew up on a small isolated commune, and his family continues to observe ancient ‘midsummer’ rituals. Despite his initial reluctance, Christian allows Dani to come with them, and before long the friends are happily taking part in psychedelic mushroom trips, experiencing the commune’s curious customs, and wearing a nice line in white linen smocks. Of course, as always happens in films like this, the charming quaintness quickly descends into chaos, as the true nature of the commune and its inhabitants is revealed.

Midsommar is a disturbing film, made all the more unsettling by the fact that it is shot in beautiful sun-dappled color; there are no dark corners to hide in here – everything is right there, brightly illuminated in an unflinching golden glow. There is some truly grotesque and horrifying imagery here, especially in the film’s second half, but what makes Midsommar also a great film is its deeper examinations of Dani’s emotions; specifically, the trauma she feels following the death of her family, and the abandonment she feels due to Christian’s neglect. Her experiences at the commune are both nightmarish but also comforting; she seems to find a sense of community and kinship there that she never found at home, and the tug-of-war that goes on in her mind – she is repulsed and attracted in equal measure – is one of the film’s main thematic ideas. Although what goes on at the commune is undeniably horrific, it also clearly has an alluring side, and this is something that pulls at Dani throughout the film.

The score for Midsommar is by the young British composer and musician Bobby Krlic, who records and releases dark ambient instrumental music under the stage name The Haxan Cloak, and also produces music for other artists such as Björk, Goldfrapp, and Troye Sivan. Krlic began writing film music only fairly recently; he contributed additional music to Atticus Ross’s score for the thriller Triple 9, and scored episodes of the network TV shows Seven Seconds, Shooter, and The Enemy Within, all following his relocation to Los Angeles in 2016, but Midsommar represents his first solo film score. My wife and I watched The Enemy Within and, I am slightly ashamed to admit, constantly made fun of the score for its overly-simplistic rhythmic ideas and mind-numbingly dull pervasive drones. As such, when I found out that Krlic had been hired to score Midsommar, I was not enthused, especially considering the style of music director Aster commissioned for Hereditary from composer Colin Stetson. This is why the end result is so unexpectedly satisfying – it plays like an orchestral depiction of a fever dream, a shocking hallucination filled with blood and bashed-in skulls, flowers and fields, fire and entrails, brilliant blue skies and warming sunshine.

Tonally, the score reminds me very much of something Jonny Greenwood might have written for a film like this. Krlic uses a fairly small musical ensemble – strings, keyboards, vocals, a couple of specialty instruments – and writes music that is almost entirely bereft of thematic content. Instead, the score unfolds like a series of trancelike vignettes, each one designed to shock or soothe, depending on what mood the director was intending at the time.

The first cue, “Prophesy,” plays over the opening credits, a Bayeux Tapestry-like animated sequence which foreshadows many of the film’s events with harp glissandi, processed organs, and faraway vocals. The subsequent “Gassed” is the musical depiction of the murder-suicide that so traumatizes Dani; Krlic uses a combination of string harmonics and slowly pulsating electronic drones which overlap in a hugely dissonant manner. At times the music twitches in agony and threatens to collapse in on itself, but by the end of the cue the music has become rhythmic and insistent, with added driving percussion, and the eerie sound of sampled wails in the background.

Once all this is over, the action shifts to the Swedish countryside. The pastoral locale of the commune, and the outwardly friendly and welcoming villagers, tends to be scored with a combination of light, bucolic string and harp textures accompanied by dreamy, detached synth drones and processed voices, as typified by cues such as “Hålsingland,” “The House that Hårga Built,” and “The Blessing”. The first of these three underscores the drive through rural Sweden the four friends undertake to reach the commune, and here Krlic does hint at the horror to come with some slightly more ominous textures, and (at the very end) a shocking interjection from a bank of screaming strings. The latter ends with a searching, near-religioso string figure that touches on the good, spiritual, naturalistic side of life in the commune.

However, the most disturbing aspects of the commune are scored with an array of highly impressionistic, challenging, occasionally downright distressing music. Cues like “Ättestupan” (which underscores the movie’s most grisly scene), “Ritual in Transfigured Time,” and “Murder (Mystery)” are filled with increasingly agitated electronic drones, grating orchestral string tones, and even sequences where the music howls and moans. The latter of these cues also includes some spooky piano writing – including moments of extended technique, such as hammering on the body of the instrument – and whining horns. “Hårga, Collapsing” is interesting because it returns to the highly dissonant Jonny Greenwood-style overlapping strings from the “Gassed” cue, drawing musical parallels between the terrible events of Dani’s life at home and the terrible events in the commune. None of this music is pleasant to listen to in any way, but it works like gangbusters in context.

“Chorus of Sirens” and “A Language of Sex” both underscore one of the film’s most shocking and challenging scenes, where Christian is coerced into taking part in a fertility ceremony with one of the commune’s young women, as a large group of older women stand and watch. Dani stumbles on the sex ritual taking place and flees, eventually succumbing to a panic attack. Krlic’s music uses ominous drones and ritualistic humming which eventually grows to incorporate increasingly intense screaming sounds: half of them are writhing in orgasmic ecstasy with Christian, while the other half are howling in anguish like Dani’s primal scream of betrayal.

The films shocking finale, which I won’t describe, is underscored by the nine-minute cue “Fire Temple,” a hypnotic piece for strings and subtle choir that slowly and gracefully emerges from a bed of impressionism into a clear, identifiable five-note motif for strings that, for some reason, has the merest hint of Maurice Jarre to it. As the scene unfolds Krlic’s music takes on a quality that almost has a cathartic, cleansing tone, but it never stops developing, and by the end it feels almost as if it has been touched by madness; the five note motif gradually gets buried in a dizzying array of accompanying tones and textures which eventually overwhelm and crush it dead. It’s quite brilliant in context, but makes for challenging listening.

The one thing the score for Midsommar doesn’t have is any folk music, which is perhaps a little unusual considering how much traditional and ancient folk music often plays in these pagan ancient rituals. The film actually contains a great deal of it – merry little melodies featuring recorders and pipes, fiddles, accordions, and tapped percussion – but none of it seems to have been written by Krlic, which leads me to assume that they are all actual folk tunes which the director licensed for the film. Similarly, some of the traditional vocal songs heard in the film appear to take their inspiration from the old-fashioned practice of kulning, traditional Scandinavian calls and chants which were historically used to call livestock down from high mountain pastures where they had been grazing during the day. It would have been interesting to hear these tracks on the soundtrack CD, to give a more rounded and complete depiction of the music heard in the film, but we can’t have everything.

Contrary to all expectation, Midsommar makes for a quite fascinating film score, which suits the film absolutely perfectly, and makes for a challenging but engrossing listen. While I’m sure many traditional soundtrack fans will find parts of the score much too difficult and dissonant to glean any enjoyment from, and while others will decry its lack of recurring thematic content, I nevertheless have to give it a hesitant recommendation, especially to anyone who derives intellectual stimulation from scores written by people like Jonny Greenwood. Considering his lack of overall cinematic experience, and bearing in mind the preconceptions I had based on hearing his score for The Enemy Within, I found this to be a deeply impressive mainstream debut from Bobby Krlic, and I am quite eager to see where he goes from here.

Buy the Midsommar soundtrack from the Movie Music UK Store

Track Listing:

- Prophesy (0:33)

- Gassed (4:29)

- Hålsingland (3:06)

- The House that Hårga Built (3:33)

- Ättestupan (3:31)

- Ritual In Transfigured Time (1:28)

- Murder (Mystery) (6:15)

- The Blessing (3:05)

- Chorus of Sirens (1:38)

- A Language of Sex (0:45)

- Hårga, Collapsing (2:41)

- Fire Temple (9:35)

Running Time: 40 minutes 38 seconds

Milan (2019)

Music composed by Bobby Krlic. Conducted by Ben Foster. Orchestrations by Finn McNicholas. Recorded and mixed by Adam Miller and György Mohai. Edited by Colin Alexanderand Michael Brake. Album produced by Bobby Krlic.